Note: For an optimal reading experience, please ensure your browser is rendering the page at 100% zoom ("Cmd/Ctrl +/-").

Essays

I. WEIMAR INTERNATIONAL

II. FILM & MEDIA THEORY

III. NEW HISTORIES

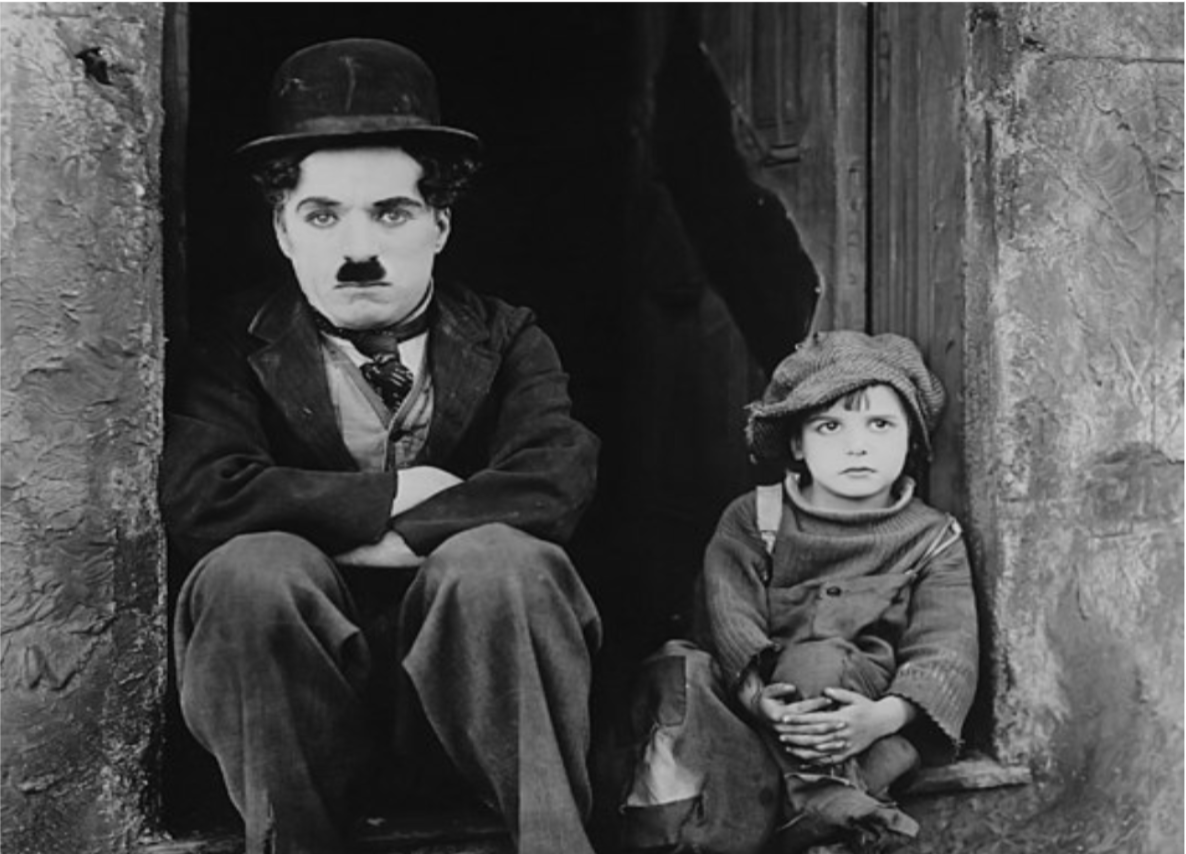

The Promise of Chaplin

PAUL FLAIG

T he fifth and final act of Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (1927) begins at the close of day, as electric lights stream from apartment windows, film palaces and car headlights. Ruttmann shifts from rain-swept, glistening streets to crowded sidewalks, as people go up and down one of Berlin’s most fashionable thorough-fairs, Tauentzienstrasse, looking for an evening’s entertainment. Such entertainment is represented first and foremost by the cinema, as we see the impressive facades of the Berliner Kino and the Atrium, the latter’s awning advertising in dazzling lights the New Woman-themed romantic comedy, Venus im Frack (Land, 1927). Outside a series of smaller, storefront cinemas, so-called Ladenkino, a placard for American cowboy Tom Mix and photographs of other movie stars surround a box office busy with customers queuing for tickets or waiting for their film-going companions. For Berlin’s own audience, a sense of expectation builds as we wonder what film and which stars these surrogates for ourselves are seeking inside the cinema. Concluding the film-themed introduction to his final act, Ruttmann shows, in a quick glimpse lasting no more than five seconds, the interior of a cramped Ladenkino to give an answer: a pair of all too familiar, ragged and over-sized shoes gambol forward, accompanied by equally iconic bamboo cane and baggy trousers.

The Letter Kills: Samuel Beckett's Debt to Fritz Lang's Films

TATJANA HRAMOVA

In the memory of Prof. Viktors Freibergs, a teacher and friend

Abstract: The world of Fritz Lang’s films is the world of shadows, mirrors and reflections; it is the world of letters and signs that wait to be deciphered – of names that multiply, echo and resonate but often do not fit. In all this – and in the innovative use of technology – Lang seems to have been an important influence on Samuel Beckett. This article attempts to illustrate this influence and show that the themes that the director investigates, especially in his films M and The Testament of Dr Mabuse, are central for Beckett’s œuvre. It becomes particularly evident in the way Beckett uses the letter M, the main feature of which seem to lie in its connection to the Other, the Not-I, a connection that was established by Fritz Lang in his thirteenth film M. Constantly resisting naming, Lang was the first to split the letter M into the W/M siglum, to dismember and reassemble the names into anagrams and letters, and to refuse to give a formal title to one of his films. Acknowledging this and identifying allusions to Lang’s films may help one to see some of Beckett’s famous lines, his characters and texts afresh.

In her biography of Samuel Beckett, Deidre Bair mentions that ‘Beckett had chosen Murphy as the title ... because he had loved Fritz Lang’s movie M and wanted to pay it homage in some...

Weimar Noir: "Lounge time" in the Cinema of G.W. Pabst

PAMELA HUTCHINSON

Austrian-born director Georg Wilhelm Pabst, who made some of the most fascinating, and darkly disillusioned films produced in Berlin during the Weimar period, registered one ill- fated foray into Hollywood in 1933-5. There he directed just one film, A Modern Hero (1934), a Pre-code tale of ruthless social climbing and sexual exploitation, but clashed with the Warner Bros studio management,1 which reinforced his existing low opinion of American commercial cinema. In fact, after working more happily in Paris, he returned to Germany (called back, he said, for family reasons), and worked in the Berlin film industry during the second world war. Therefore, Pabst was destined never to join the band of European emigrés who settled in Los Angeles between the wars and brought their skills and attitudes to Golden Age Hollywood cinema, and the shadowy subset known as film noir, in particular. However, the prism of Hollywood film noir, and one theorist’s way of dissecting the construction of films made in this mode, may throw some light on the work of Pabst, and his understanding of the spaces of Weimar Berlin, the wreckage of post-war, post- revolutionary Europe and underworlds both metaphorical and literal, from casinos and nightclubs to coal mines, trenches and the lost city of Atlantis.

Queer Cinema in Weimar Germany

SO MAYER

As the doctor in Anders [als die Andern] tells Paul’s parents: “It is neither a vice nor a crime, nor even a sickness, but a variation, one of the borderline cases in which nature is so rich.”

— Richard Dyer, 20.

Richard Dyer’s 1990 path-breaking article “Less and More than Women and Men: Lesbian and Gay Cinema in Weimar Germany” definitively added the complex nexus of genders and sexualities to the rich field of Weimar cinema studies.1 Dyer offers a dual historical evaluation that places film critical writing on Anders als die Andern (Richard Oswald, 1919) and Mädchen in Uniform (Leontine Sagan, 1932) and contemporaneous sexological, sociological and popular understandings of gender and sexuality side by side, showing the gap between the appraisal of the films and their place in a cultural continuum of queerness. His meticulous research and exquisite readings implicitly demonstrate both the lack of lesbian and gay film criticism on Weimar cinema, at the time and subsequently; and the value of queer film scholarship – that is, film scholarship formulated in tandem with queer theory – for giving the fullest reading of Weimar cinema as an aesthetic, formal, social and political formation....

Cinema of Attractions

TOM GUNNING

Weimar cinema has never shaken its legacy of coming “From Caligari”, even if its identification as “Expressionist” has been subjected to endless critique. But while the complex heritage of Expressionism relates only to a few admittedly influential Weimar-era films, silent German cinema’s links to a cinema of the uncanny persists, like a half-remembered nightmare that refuses to fade. In our cultural memories, Weimar screens remain haunted (L’écran démonique). My brief contribution to this dynamic website considers Weimar’s uncanny cinema through its afterlife – or, perhaps better, its Nachklang, “echo or resonance.” I propose a fascinating film, little known outside of Germany, Frank Wysbar’s (sometimes spelled Wisbar) Fährmann Maria from 1936. Although I do not know the films of the Third Reich as well as I know the Weimar films (and perhaps other scholars could situate Wysbar’s film better than I), Fährmann Maria feels to me like a film gone astray from the earlier era. This untimely resonance draws me to the film and leads me to some speculations about the relations between eras and genres.

Cinema and Law

SARA F. HALL

T his essay was originally published in the journal Communications: The European Journal of Communication Research (2019); 44(3): 304-322, as part of a special issue on current trends in remaking European screen cultures edited by Eduard Cuelenaere, Stijn Joye and Gertjan Willems. It received the 2019 Society for Cinema and Media Studies East/Central/South European Cinemas Essay Award and has been adapted for web publication with the generous permission of De Gruyter Mouton. The author would like to acknowledge Phill Cabeen and Monty George for their assistance with the conversion.

Abstract: Centered on Richard Dyer’s model of pastiche, this essay posits that the German television series Babylon Berlin engages in a unique and timely practice of cultural reproduction shaped by a specific combination of historical subject matter and the present media-historical moment. Through digital effects, narrational layering, and multivalent location choices, Babylon Berlin pastiches Weimar cinema, and self-consciously invites comparisons between the so-called golden age of German cinema and the present. It activates cinephilic recall, establishes an intermedial dialogue between analog and digital forms, and affectively engenders a historically oriented conversation about the fragility of modern democracy in the Brexit/Trump era. Its cultural work of pastiche warrants the series’ inclusion in the conversation around the European remake.

Keywords: Weimar cinema, Babylon Berlin, remake, digital effects, democracy, pastiche

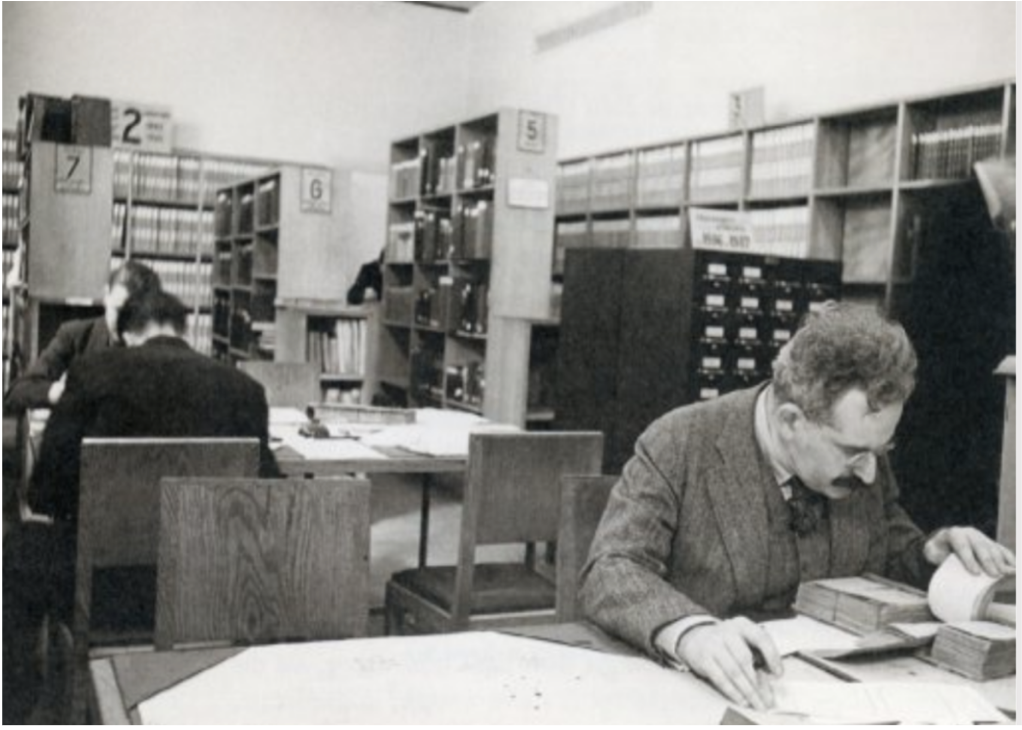

Benjamin and Film

HOWARD EILAND

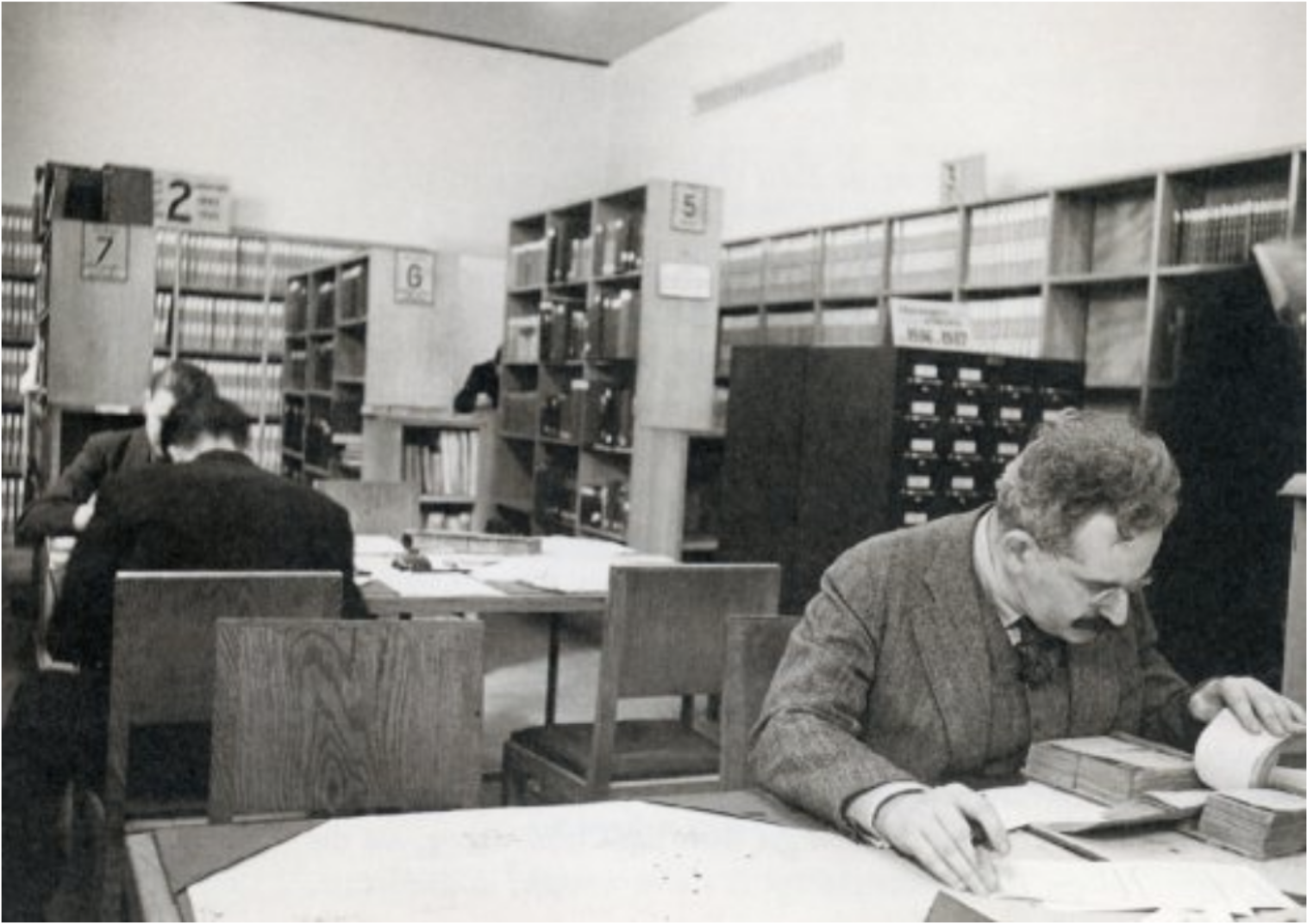

Gisèle Freund, Walter Benjamin in the Bibliothèque Nationale (1939)

A highly condensed note in The Arcades Project, dating probably from the late 1920s, offers what is possibly the broadest and boldest statement on film that we have today from Walter Benjamin. The note has its place in the context of methodological formulations concerning the temporality of historical interpretation and what is conceived of, in this serendipitous study of nineteenth-century Paris, as historical dream and historical awakening. One awakens from “that dream we name the past” only by descending back through remembrance into the convolute of the dream itself; one wakes simultaneously from and to a dream past in order to waken a present day. So historical awakening is prepared in dreaming of the past. It is nothing short of a “Copernican revolution in historical perception” that Benjamin announces here, in Convolute K of the Arcades: a momentous theoretical turn toward a dialectical method of historical remembrance pivoting on “the higher concreteness of now-being.”[1] Such perception is dialectical because it is turned toward past and present at the same time; it is their virtual convergence as monad and mutual tension in an experience of recognition. In this precipitous constellatory temporality, in which time at once shrinks and expands, the moment of remembrance is thus “preformed” in its object.

Dance and Film in Weimar Germany

KRISTINA KÖHLER

T he fact that film became an object of analysis at a time when dance, body culture and life reform movements were on the agenda has received comparatively little attention in film historical scholarship to date. Yet, especially in Germany, gymnastics and modern dance formed an important context that clearly resonated in the debates surrounding the new medium.[1] Not only were the same people—intellectuals, artists and critics—commenting on contemporary events in film and dance, but early film theory and modern dance were also surrounded by similar concerns and inquiries: When is a movement “beautiful”? What makes a body expressive? And which specific forms of a viewer’s aesthetic experience are addressed through movement?

Ripples of Sound

LUTZ KOEPNICK

Contemporary German sound artist Carsten Nicolai is internationally known for his experimental music performances and installation works such as wellenwanne (2001/2003/2008), in which water trays visualize musical sounds through changing wave and interference patterns. In fall 2015, Nicolai presented a new work of immense proportions, unitape, at the Kunstsammlungen Chemnitz. ![]() [1] Twenty-five meters in length and four meters in height, unitape puts to work different encodings of sound and music, its visual structure recalling the look of punch cards as they had first been used in the weaving industry around Chemnitz in the mid-1800s. Cascading from the gallery’s ceiling, ever-changing arrangements of quadrilateral marks trigger the production of acoustical signals, their vibrations so intense that we can literally sense them with our entire bodies.

[1] Twenty-five meters in length and four meters in height, unitape puts to work different encodings of sound and music, its visual structure recalling the look of punch cards as they had first been used in the weaving industry around Chemnitz in the mid-1800s. Cascading from the gallery’s ceiling, ever-changing arrangements of quadrilateral marks trigger the production of acoustical signals, their vibrations so intense that we can literally sense them with our entire bodies.

Radio and Film

ERIK BORN

W hich came first—cinema or television?[1] Until recently, the origins of moving images were usually taken to be synonymous with those of “the movies,” and the year 1895 was commonly considered the annus mirabilis in the history of cinema. Despite some dissenting work on the development of moving images over the millennia,[2] the date remained significant in mainstream film studies for marking at least three decisive conditions of possibility for the appearance of the medium: the availability of the cinematograph; the genesis of production and exhibition practice; and the emergence of aesthetic considerations. In television studies, on the other hand, there was never a similar consensus. Over two decades before the consolidation of cinema, there were already models for televisual machines, and the earliest patent for a mechanical television system, which looms especially large over the German historiography of television, was granted a decade prior to the first patents for cinematographic devices. Nevertheless, the promise of electronic television would remain unfulfilled throughout the anni horribiles of two world wars, an extended incubation period representing a long-standing source of irritation for media studies. As the editors of a recent collection on German Television observe, “Until the mid-twentieth century, television remained only an epistemic object, not fully realized and thus partly latent in the history of media.”[3] By extension, one of the editors wonders, “Might television be a latency or blind spot of media theory?”[4]

Marketing Expressionism in Weimar Cinema and the Applied Arts

LEONARDO QUARESIMA

The term "Expressionist film" enjoys wide currency and notoriety, yet as a definition it has been regarded with reservation. At issue is not only the appropriateness of the term but also the field the definition is supposed to designate. The borders of discussion change dramatically: sometimes they expand to embrace the entire period of German silent film, at other times they shrink to a mere handful, no more than half a dozen, films.

The uncertainty first surfaces in Siegfried Kracauer's and Lotte Eisner's classic studies on Weimar cinema published after WWII, and becomes steadily more acute with ensuing publications, through to the (not numerous) more recent studies that tend to balk when it comes to tackling the issue head-on.[1] This preamble will not rehearse old issues. Decisive transformations of the debate have taken place over the past three decades, so that to write about Expressionist film is almost a completely new undertaking now. A different concept of film archiving and a growing awareness of philological concerns have given rise to a framework that was inconceivable before. New finds in the archives, reconstructions, restorations; new approaches to questions of color, titles, and film music; and greater attention to sources as a whole (from multiple elements of a given film to the critical reception upon its release): all these elements have not so much propelled the investigation forward, as generated a transformed object of study.

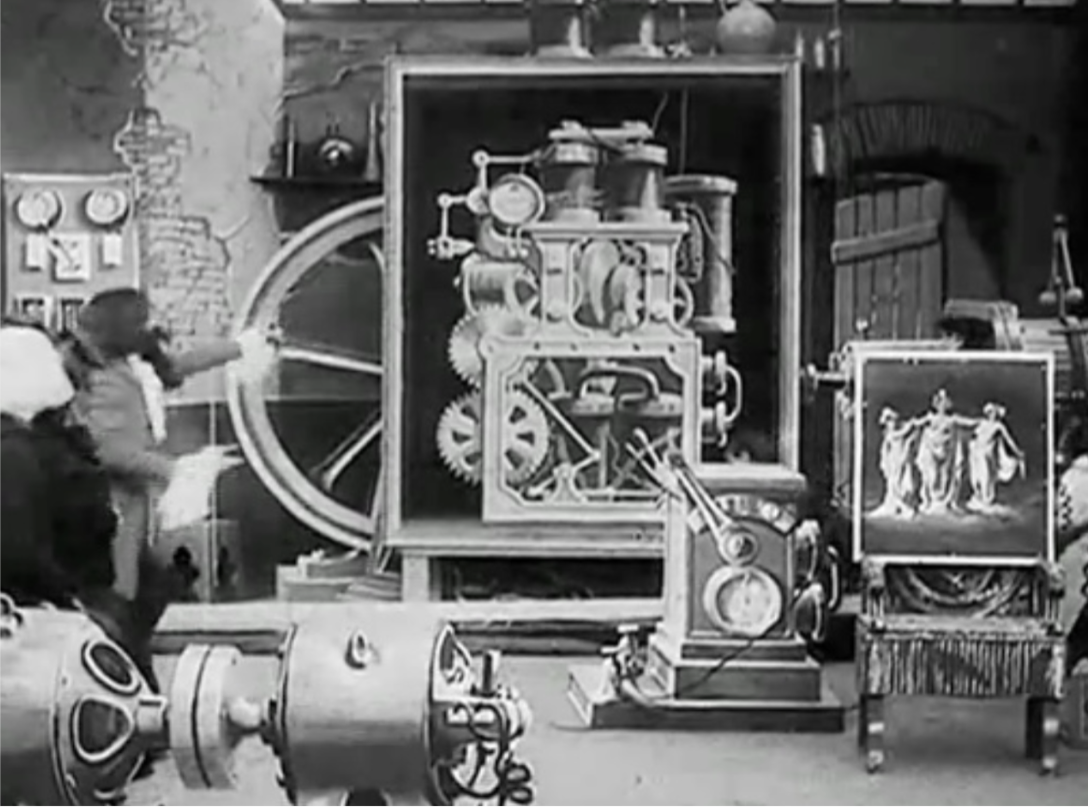

Weimar Shorts

MICHAEL COWAN and ANTON KAES

Why a program on Weimar “shorts” today?[1] One answer is that we are increasingly surrounded, in our digital media environments, by “short form” videos. Whether you trace the phenomenon back to the launch of YouTube in 2005 or the rise of music videos in the 1980s, most people are now exposed daily to a large roster of short forms, ranging from travel shows to clips of cute pets, from instructional videos to avant-garde experiments — all archived in online repositories or shared on social media platforms. Not for nothing, then, has YouTube been described as the new “cinema of attractions,” where the immersive experience of being “kidnapped” (Susan Sontag) in a darkened theater gives way to curiosity, humor, and fascination. And little wonder, also, that historical short films are being rediscovered today — not only from the days of early cinema, but also from periods after the consolidation of narrative film.

Sound Cinema

MICHAEL WEDEL

Research on Weimar cinema is becoming increasingly diverse. At one end of the spectrum are studies that follow the perspectives of the foundational accounts of Siegfried Kracauer and Lotte Eisner and focus mainly on canonized works. At the other end of the spectrum are studies, some of which break radically with conventional perspectives, juxtaposing emblematic works and their authors with a variety of little- known names, titles, and contexts. A number of new publications on the subject can be gleaned from this productive mix.

Restoring Weimar Cinema

STEFAN DRÖSSLER

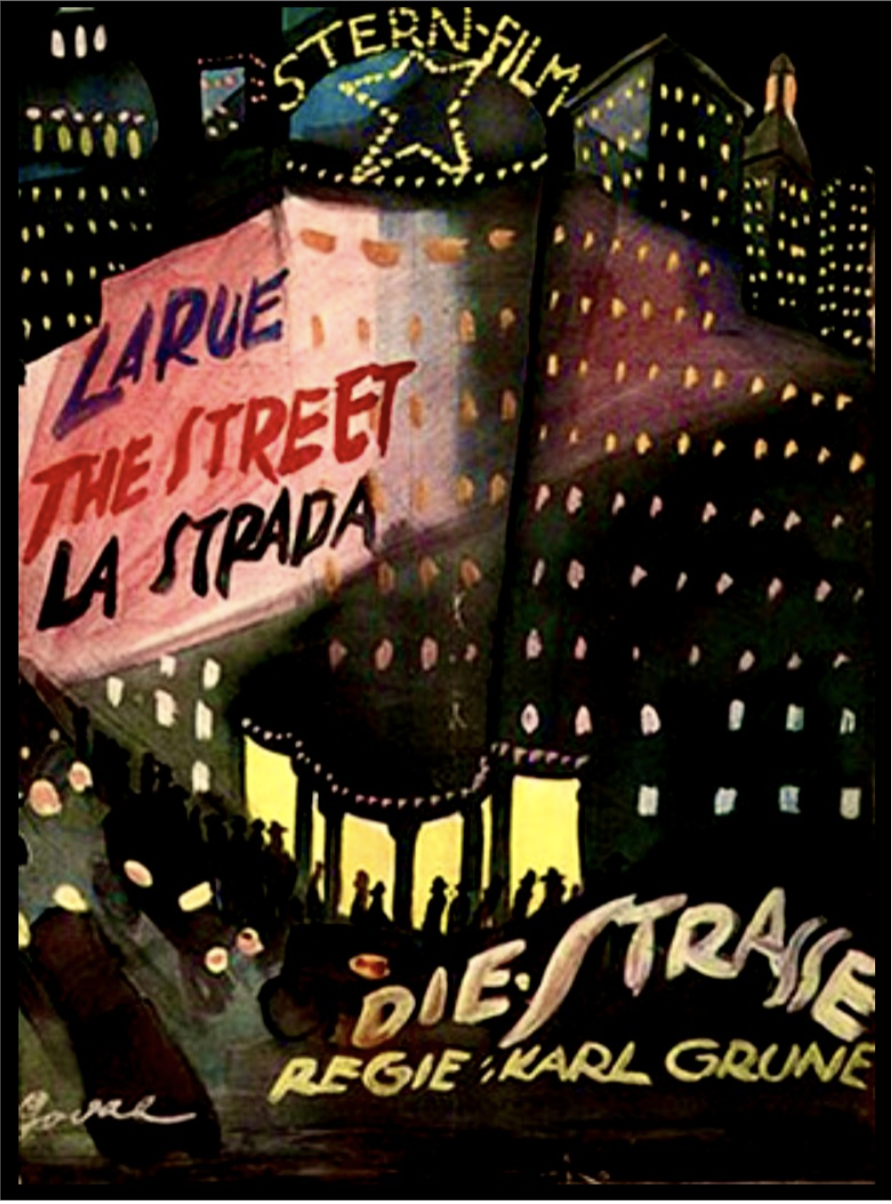

Today Karl Grune (1890-1962) is one of the lesser-known directors of German silent film, but he was once placed by contemporary critics in the forefront of European film artists. He owes this above all to Die Straße, which is considered his most important work. Siegfried Kracauer published two reviews upon its Frankfurt premiere, and repeatedly cited it in his writings as a key film, which founded the “street film” genre. In his book From Caligari to Hitler, he defines

Film Archives

HANS HELMUT PRINZLER

“If only I had the cinema!!”– note the two striking exclamation points – was the title of a pamphlet by Carlo Mierendorff, published in 1920, a title that abides today as a topic of interest, as a headline, almost as a mantra. But we still have it, the cinema. We still have it. We just have to make sure that the day will not come when it suddenly disappears. And we must constantly bear in mind this resolve.

Women in Early German Cinema

HEIDE SCHLÜPMAN

Film history, silent film, early cinema: I have researched and published in these areas, and I have tried to keep history present while teaching and engaging with film curatorial work. But the merits of my contributions to film history are small compared to what film history has done for me, along with it the multitude of those who have made it possible for me to encounter films over and over again. Film history has broadened my perception, changed my relationship to the world, changed my thinking, and changed my life.

On Daniel Kehlmann's LICHTSPIEL

BRENDA BENTHIEN

Best-selling German novelist Daniel Kehlmann has written a cinematic tour de force, a surreal and atmospheric reimagining of the anguished and peripatetic later life of legendary Austrian film director G.W. Pabst. The book's title is aptly chosen: "Lichtspiel" is an old-fashioned word for "film" that also refers to a "play of light." An English language translation of the novel is scheduled for publication around summer 2025 by Quercus in the UK and Summit Books in the US and Canada.

G.W.'s Legacy

BRENDA BENTHIEN

A new documentary explores G.W. Pabst's legacy through his grandchildren. From 2024, Angela Christlieb's Pandora's Legacy weaves together Trude Pabst's letters, dream writings, and film excerpts with interviews of Pabst's descendants, creating a mosaic portrait of the filmmaker's family and artistic influence.