Note: For an optimal reading experience, please ensure your browser is rendering the page at 100% zoom ("Cmd/Ctrl +/-").

"The Promise of Chaplin"

Paul Flaig

T he fifth and final act of Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin: Symphony of a Great City (1927) begins at the close of day, as electric lights stream from apartment windows, film palaces and car headlights. Ruttmann shifts from rain-swept, glistening streets to crowded sidewalks, as people go up and down one of Berlin’s most fashionable thorough-fairs, Tauentzienstrasse, looking for an evening’s entertainment. Such entertainment is represented first and foremost by the cinema, as we see the impressive facades of the Berliner Kino and the Atrium, the latter’s awning advertising in dazzling lights the New Woman-themed romantic comedy, Venus im Frack (Land, 1927). Outside a series of smaller, storefront cinemas, so-called Ladenkino, a placard for American cowboy Tom Mix and photographs of other movie stars surround a box office busy with customers queuing for tickets or waiting for their film-going companions. For Berlin’s own audience, a sense of expectation builds as we wonder what film and which stars these surrogates for ourselves are seeking inside the cinema. Concluding the film-themed introduction to his final act, Ruttmann shows, in a quick glimpse lasting no more than five seconds, the interior of a cramped Ladenkino to give an answer: a pair of all too familiar, ragged and over-sized shoes gambol forward, accompanied by equally iconic bamboo cane and baggy trousers.

This synechdochal flash of Charlie Chaplin’s Tramp, as instantly recognizable to viewers in 1927 as in 2016, is a brilliant stroke on Ruttmann’s part. It allows him to stick to his documentary impulse of capturing Berliners at evening play—we see silhouettes of a boisterous, amused and chatty audience—while simultaneously depicting on only an eighth of film screen a figure immediately identifiable even when deprived of torso or face. Yet this balance between the time and space of metropolitan Berlin and that of the American slapstick film—the only moment in Ruttmann’s city-symphony in which film itself is seen—is also meant to tell us something about the singular importance of Chaplin and his Tramp for Berliners in the nineteen-twenties. In contrast to Dziga Vertov’s The Man with the Movie Camera (1929), influenced by Berlin yet concluding with a public screening of its own preceding imagery, Ruttmann pphasizes the promise of cinema through the promise of Chaplin as star, filmmaker and iconic image for German audiences. While Ruttmann performs this promise largely through a formal strategy of city-symphonic montage, he chooses as a kind of emblem of cinema neither his own images nor those of another German film (say, Venus im Frack), but rather the partial-image of Chaplin, by 1927 still the most popular and recognizable film star in the world.

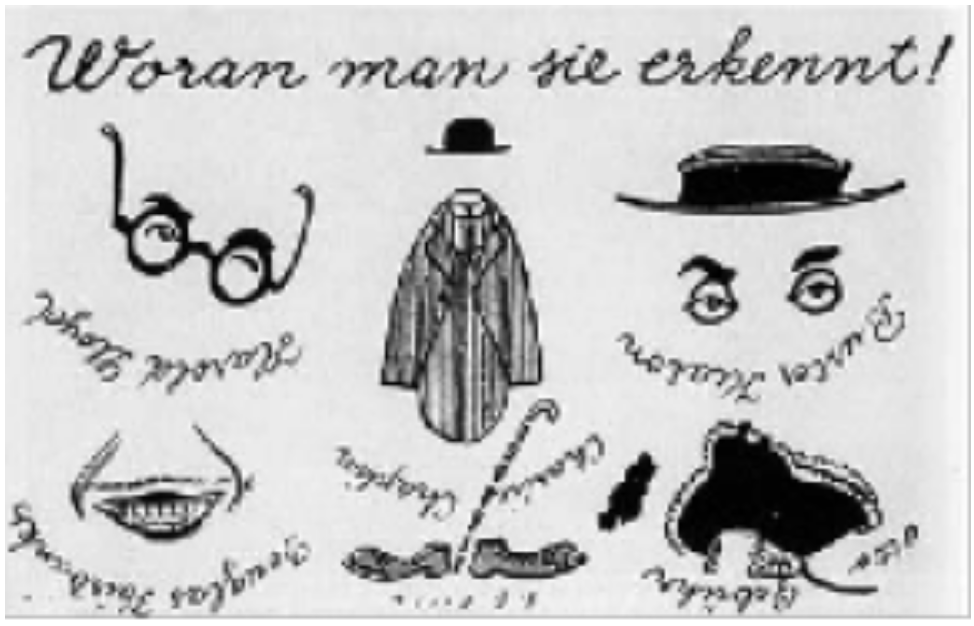

One of the great pleasures in reading The Promise of Cinema comes from noticing recurring leitmotifs spanning its pages, finding in the movement across periods, technologies and concepts symptomatic desires and tensions circulating between screen, spectator and reader. Following such a transversal reading, Charlie Chaplin appears as one of the volume’s most visibly recurrent figures. This circulation cannot help but recall the Tramp’s anarchic movement in and out of the movie projector-like assembly line in Modern Times (1936) or, for that matter, the animated shoes and cane given cameo in Ruttmann’s Berlin: Symphony of a Great City. Indeed, the latter’s disjointed, broken animation exceed, by virtue of both Chaplin’s performance and Ruttmann’s framing, control of mind or body to become wish-images evocative in their own right, much like the shoes, cane, baggy trousers, right vest, mustache dot and bowler which made up the Tramp assemblage.

I’d like to briefly track such images and evocations as they circulate within The Promise of Cinema. This interest comes in part from my own research, specifically a forthcoming monograph entitled Weimar Slapstick: American Eccentrics, German Grotesques and Hollywood Comedy Re-Functioned, which examines appropriations of American slapstick cinema within visual, political and intellectual cultures of the Weimar Republic. I am also the co-editor with Katherine Groo of the recent collection, New Silent Cinema, which examines returns to silent and early cinemas in contemporary digital culture. In the spirit of both projects, I will discuss how cinema’s various promises and possibilities were negotiated through Chaplin’s films as they were understood by diverse German critics, artists and filmmakers. I want to examine Chaplin as a figure of promise itself, as a reminder for both Weimar critics and contemporary readers of The Promise of Cinema of how the anarchic, anachronistic Tramp could reveal alternative possibilities for the cinema beyond traditions from the past, definitions of the present, or sureties about the future.

Approaching Chaplin as this figure of promise, Siegfried Kracauer, in “Chaplin in Old Films,” examines a 1930 revival of Tramp comedies from the teens, arguing that “the little cane, the tattered boots, and the whole vagabond costume with the baggy pants” are crucial contributions to these films’ utopian if anachronistic “fairy tale atmosphere” (400). For Kracauer, such wish-images offer a redemptive vision of the lumpenproletarian outcast as angelic prince. These now “old films” also redeem cinema itself, offering viewers haunting images of the forking paths not subsequently taken in film history, “the other possibilities that would not necessarily lead to later reality.”

Read with the Tramp’s cameo in Berlin, Kracauer’s retroactive, redeeming appeal to the promise of Chaplin offers readers of The Promise of Cinema a useful method for understanding how and why these two promises so often correspond across the latter’s treasure trove of texts. Tracking Chaplin’s circulation and citation throughout the collection, one finds not one promise but many, a wide-range of reflections on both what cinema is or will be, but also what it was and might otherwise have been. This is as true in Kracauer’s appeal to the early Chaplin, his status as “old” consolidated only by the presence of new genres as much as new media (synchronized sound, radio, color, television etc.), as it is for Ruttmann, where the film in question seems to come from an unidentified short from the teens rather than the contemporary The Gold Rush (1926). “Promise” thus implies the virtual as much as the actual, the potential as much as the empirical, the future as much as the past. The particular promise of Chaplin offers intense, varied and often contradictory claims on both then contemporary practices of filmmaking or film-going as well as the utopian or dystopian possibilities embedded in the Tramp’s partial-objects and wish-images. In Berlin: Symphony of a Great City, for instance, Ruttmann balances documentation of Chaplin’s popularity with his own appeal to Chaplin’s synecdochal feet and cane as synecdoches of cinema. This avant-garde engagement with slapstick, mingling wish-images with a range of artistic practices, is comparable to Kracauer’s call for his readers to re-watch Chaplin’s “old films” not as bygone relics of a vanished age, but as suggesting alternative paths for the cinema, “other possibilities” to be actualized against the political and aesthetic dogmas of present and progress.

This mingling of the citational and the performative, the actual and virtual, can be found among so many references to Chaplin in The Promise of Cinema: Albrecht Viktor Blum’s appeal to Chaplin’s idea-driven “‘fairy-tales of reality’” (“Documentary and Artistic Film,” 103-104); Robert Musil’s locating the Tramp within a broader comic tradition giving rise to the cinema and its uniquely embodied, synaesthetic spectatorship (“Impressions of a Naïf,” 323-324); Kurt Pinthus celebrating the universal quality of Chaplin’s films, which unburdens spectators through comedy and in doing so lets them recognize underlying tragedies (“The Ethical Potential of Film,” 389); G.W. Pabst’s predictive claim that Chaplin is the only contemporary filmmaker who will “leave behind his ‘collected works’” (“Film and Conviction,” 376). Other references to Chaplin in The Promise of Cinema focus on topics ranging from movie star gossip to the technology of sound film to cinema’s ambivalent status as art to the perceived deficiencies of German film comedy as illuminated by slapstick.

In the case of Berlin, it is not surprising that Ruttmann would identify the promise of cinema through, on the one hand, his own formal practice of musical, metropolitan montage and, on the other, the citational image of Chaplin’s feet and cane. For many, the Tramp was the very emblem of cinematic montage. This montage was performed or suggested on several levels: in the various and disjunctive parts that formed his costume and mask; in a jerky, neurasthenic body; in the unruly effects this body unleashed across often urban settings. Ruttmann’s citation was as much a documentation of Chaplin’s German popularity as a projection of his own desire for cinema’s promise, innervating his audiences by drawing on the energies of the Tramp, who thereby becomes a figure of kinship and correspondence between Hollywood and Berlin, urban masses and the avant-garde, city-symphony and slapstick comedy. After all, it is difficult to tell what is animating the audience more, the Tramp caterwauling on screen or the presence of Ruttmann’s camera filming from behind.

Walter Benjamin, like Ruttman, found in the Tramp’s “succession of staccato bits of movement” and gestural confusions the very principle of cinematic montage, a continuous sequence of discontinuous, broken images revealing a shared materialist logic between cinema and the assembly line. Anticipating Benjamin, many German critics would argue for this crucial link between cinematic form, industrial technology and the Tramp. Axel Eggebrecht, for instance, argues that Chaplin, unburdened by theatrical traditions, could approach cinema for what it is, at once “purely visual” and a “representational form of the industrial machine age” (“The Twilight of Film,” 302).

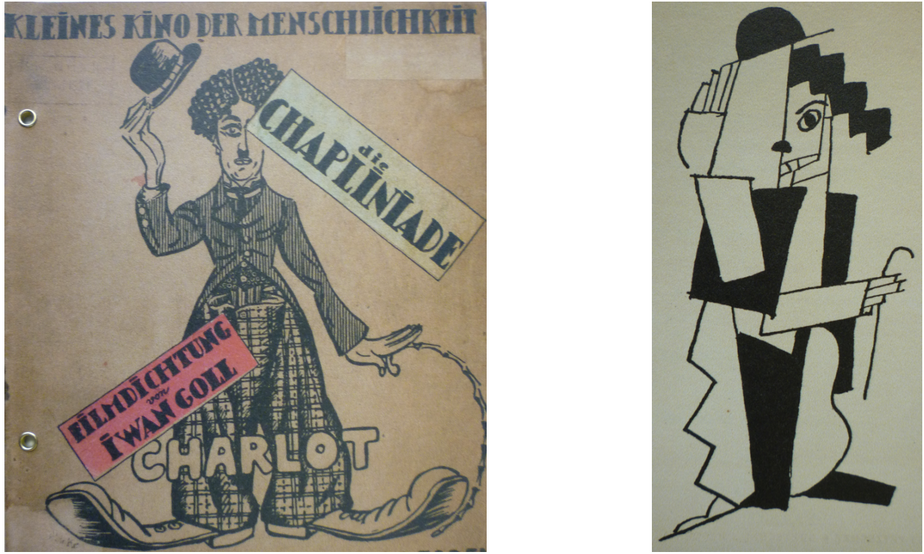

Fernand Léger’s illustration for Yvan Goll’s Die Chaplinade: Eine Kinodichtung (1920)

Chaplin’s own explicit turn to the assembly line in Modern Times reads to the contemporary critic like a too literal interpretation of Benjamin’s claims about the Tramp as much as it might have evoked to the 1936 cinephile René Clair’s À Nous la Liberté. Clair would himself claim to have been inspired by Chaplin well before his film inspired Modern Times and his Dadaist compatriots in both France and Germany would likewise identify the Tramp as a cipher of industrial montage, perhaps most famously in the animated opening of Fernand Léger’s Ballet Mécanique (1924). Beyond the French Dadaist and Surrealist celebrations of the slapstick star, we find this montage version of the Tramp depicted most often in various German avant-gardes. Indeed, Léger’s first, fractured images of the Tramp would accompany Yvan Goll’s 1920 poem, Die Chaplinade: Eine Kinodichtung while his film would have its premiere at the 1924 Internationale Ausstellung für Theatertechnik in Vienna. This event was organized by the designer Friedrich Kiesler, who would himself bring this German slapstick fandom to the United States, the inaugural screening at his Bauhaus-inspired cinema, the Guild Theater in New York, including Chaplin’s 1916 short, 1 A.M. Members of the Bauhaus would also appeal to Chaplin’s eccentric: Oskar Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet was partially inspired by Chaplin’s marionette-like motion while László Moholy-Nagy used the filmmaker as a role model for communicating directly to mass audiences rather than constructing ideal versions thereof. Among Berlin Dadaists, Chaplin would be oft cited in montages and paintings and oft celebrated in manifestoes and journals.

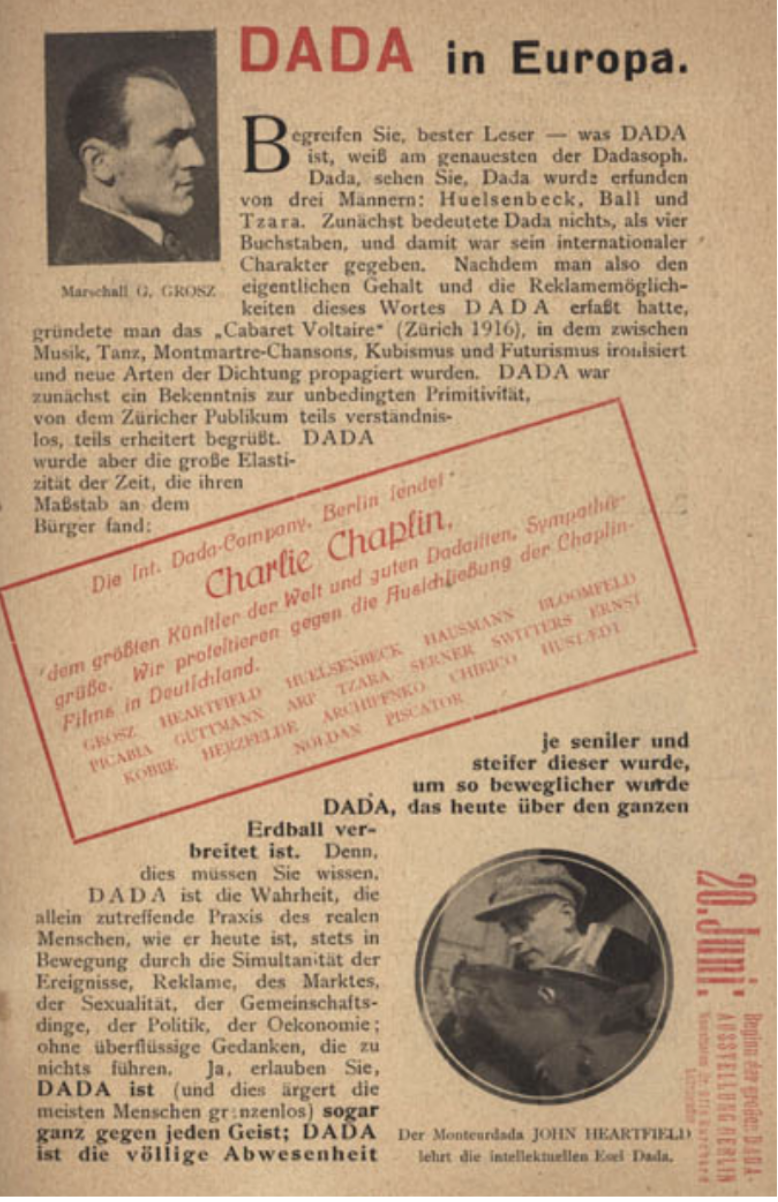

“The int. Dada-Company, Berlin sends sympathetic greetings to CHARLIE CHAPLIN, the greatest artist in the world and a good Dadaist. We protest the exclusion of Chaplin films in Germany.” Der Dada No. 3 (April, 1920)

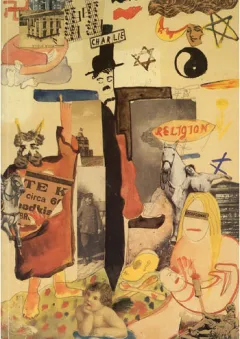

George Grosz would identify with Chaplin in self-portraits and dedications; Otto Schmalhausen converted Beethoven’s death mask into a portrait of the Tramp for the 1920 International Dada Fair; Johannes Baader painted an “Honorary Portrait of Charlie Chaplin” which doubled as a “tribute” to Gutenberg’s invention of printed type and thus claimed for film and its greatest representative an equally revolutionary power; Gerhard Preiss, the “Music Dada” exhibited a series of photographs of himself in bowler hat and black clothing dancing the “Dada-Trott,” a dance that cannot help but recall the Tramp’s own derby-bedecked displays; Erwin Blumenfeld dubbed himself “President-Dada-Chaplinist” and produced a montage of the slapstick comedian simultaneously lying on and becoming the Christian cross, surrounded by various religious and art icons, including the Star of David and Swastika.

Dada Collage (Charlie Chaplin), Erwin Blumenfeld (1921)

One of the most astute critics of Berlin Dada, Adolf Behne, in “The Public’s Attitude toward Modern German Literature” (392-394), would echo these works, hailing Edison as “the new Gutenberg” and Chaplin as the greatest practitioner of “film as an art of the masses.” In these and other essays (“Film as a Work of Art,” 457-458) Behne distances cinema from traditional aesthetic forms and judgments, suggesting that in place of “the individual artwork” Chaplin’s cinema offers a political, democratic and didactic mode fit for elevating the masses rather than subjecting them to the hierarchies of taste or the folderol of kitsch. Anticipating Benjamin’s later and by now oft cited claim about the affinities between slapstick and the avant-garde in “The Work of Art in the Age of its Technical Reproducibility,” Behne sketches a range of ideas all too familiar to readers of that famous essay: the politicization of aesthetics through a kind of “didactic literature” (394); the dissolution of the traditional artwork; the construction of a shared, democratic sensorium; continuities between avant-garde shock and mass popular gag.

A more direct anticipation of “The Work of Art” essay comes in Theodor Adorno’s “Kierkegaard Prophesies Chaplin” (401-402). Indeed, it is more than likely that this short piece for the Frankfurter Zeitung would influence the former text’s reflections on cinema (a mutual friend and Chaplin fan, Kracauer, had arranged for this essay to be published and sections of Adorno’s Habilitation on Kierkegaard would be cited in Benjamin’s Passagen-Werk). Described, following Kierkegaard, as “The one who comes walking,” Chaplin is here understood in terms of mimetic faculty, not only “able to walk,” but to cite walking as a kind of Brechtian Gestus, presenting the most basic of physical motions as animated prop, identifiable (and comical) in much the same manner as the partial objects comprising the Tramp’s costume.

This emphasis on mimesis, prop and gesture through the example of walking recurs in the well-known section on the “optical unconscious” in “The Work of Art”: “…we have some idea what is involved in the act of walking (if only in general terms), we have no idea at all what happens during the split second when a person actually takes a step.” Because of the “jerky” montage that was the Tramp’s walk, comically fractured between the imitation of an ostentatious leisure class, on the one hand, and rude antics and material deprivations of the lumpenproletarian on the other, this moment of taking a step or coming walking, is made simultaneously visible, laughable and thinkable. As Ruttmann intimates with his own citation of Tramp and spectator, this walk is also cinematic, identifying gestures by breaking them down into their constitutive parts, asking actors and audiences to look at themselves through the estranging, testing gaze of the camera. While this “split second” has usually been related to the precedents of Marey or Muybridge, the simple motion of taking a step was a common example in Weimar reflections on slapstick. Benjamin’s colleague in Hans Richter’s G group, the Dadaist Raoul Hausmann praised both Chaplin and Keaton and would emphasize, in both articles and his own dance performances, that to see, feel or think the gesture of “walking” one must have a cinematic “consciousness of lightning-quick rapidity [blitzartiger Schnelle].” The distant, almost scientific view afforded by slapstick’s gestics would likewise earn the praise of another colleague, Bertolt Brecht, who claimed that Chaplin’s films “depict the human being as an object and could have an audience entirely made up of reflexologists.” Yet this objection would also provoke suspicions of sadism, at the other end of the political spectrum, in the writings of Ernst Jünger. In a passage from Der Arbeiter included in The Promise of Cinema (408-412), Jünger views slapstick as an aggressive assault of the type over the individual, at once a modern sign of technology’s victory over a human reduced to “plaything” and civilization’s regression to primitive, tribal warfare.

Stumbling at this dense intersection of epic theater, messianic Marxism, conservative critique, Dadaism, Neue Sachlichkeit, psychoanalysis, National Socialism, psychophysics, and film industries, Chaplin provokes fervent and often antinomial interpretations and appropriations across The Promise of Cinema. Written in the wake of debates running throughout the collection, the famous case of “The Work of Art in the Age of its Technical Reproducibility” offers such antinomies on a page by page basis, with Benjamin following Brecht’s behaviorist appeal to slapstick while, in a footnote, critiquing Chaplin’s heir apparent, Mickey Mouse, for the “cozy acceptance of bestiality and violence as inevitable concomitants of existence,” an acceptance Benjamin saw as reviving the carnivalesque iconography of medieval pogroms. This reservation about slapstick, situated somewhere between Jünger’s critique and Adorno’s description of Chaplin’s “bestial quality” and “cruelty” (in a later addendum to “Kierkegaard Prophesies Chaplin,” written after the critical theorist’s comic encounter with the filmmaker in Malibu) follows larger discussions of cinema, slapstick and Chaplin within the Republic’s media-sphere, with suspicions arising among the members of both Nazi and Communist parties, celebrations among conservatives, liberals and leftists, imitations as well as resistances on the part of various filmmakers, performers and audiences. This is not to mention the fraught ethnic politics surrounding Chaplin’s perceived Jewishness (never mind that of the Tramp or indeed Mickey Mouse), which one finds in the anti-fascist caricatures of Karl Arnold, the censorship policies of Josef Goebbels and in Hannah Arendt’s theory of the refugee. Or, at the seeming other end of the spectrum, the Tramp’s evocation, for both Kurt Tucholsky and Benjamin, of the petit-bourgeois mannerisms and “diminished masculinity” of Hitler, with whom this character shared, for both, far more than a mustache. Like his descent down the assembly line, Chaplin’s double portrayal of both Jewish victim and petty tyrant in The Great Dictator (1941) would seem to implement these prior, Weimar-era interpretations of the Tramp. In the case of this film as well as Monsieur Verdoux (1946), Chaplin was in point of fact directly influenced by Weimar figures who had once been so taken with his Tramp, absorbing the caustic wit of Salka Viertel, Hanns Eisler and Brecht among others.

“In the political fight: ‘Just a Jew!’” (Simplicissimus, 1931)

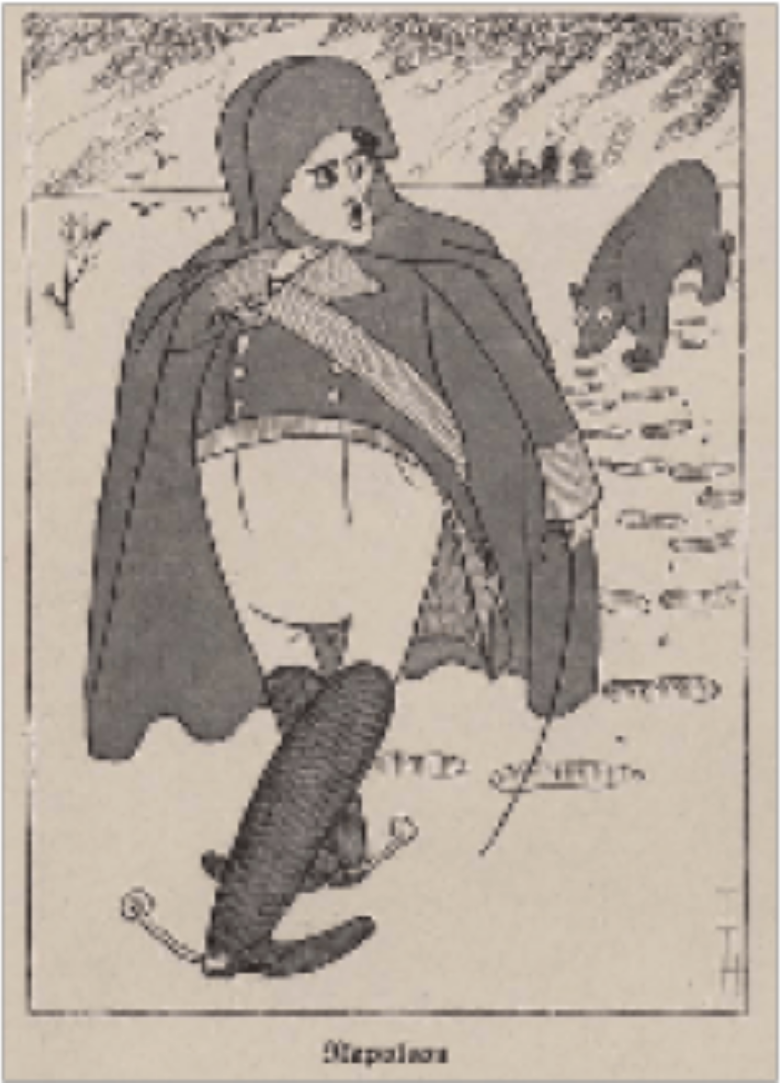

To conclude this reflection on the promise of Chaplin, I’d like to turn to another text by the antinomial Benjamin, one largely forgotten among scholars but happily included in The Promise of Cinema. Like Kracauer’s appeal to early Chaplin films’ “other possibilities” or Adorno’s description of the Tramp appearing as a “ghostly photograph in a live-action film,” Benjamin would, in “Chaplin in Retrospect” [Rückblick auf Chaplin] (398-400), emphasize the spectral, anachronistic quality of Chaplin and his cinema in The Circus (1928), made on the cusp of Hollywood’s conversion to synchronized sound. Approaching this film as itself a kind of retrospective overview of the filmmaker’s “greatest themes,” Benjamin also offers an unwitting Rückblick on the many discussions of Chaplin circulating throughout The Promise of Cinema: Chaplin’s films as idea-driven, the filmmaker’s technical sophistication, speculations about future films like the recently announced Napoleon (basis for The Great Dictator), biographical tidbits, a valorization of laughter, political interpretations of the Tramp, an emphasis on the Tramp’s popularity among diverse global audiences etc. Yet it is the beginning of this Rückblick that is perhaps most intriguing, especially in light of the no less retrospective, redemptive gaze occasioned by The Promise of Cinema.

Napoleon (Simplicissimus, 1926)

Note: We are currently in the process of restoring this media asset

Appropriately placed by the collection’s editors to precede Kracauer’s “Chaplin in Old Films,” the essay begins, “The Circus is the first product of the art of film that is also the product of old age. Charlie has grown older since his last film. But he also acts old. And the most moving thing about this new film is the feeling that Chaplin now has a clear overview of his possibilities and is resolved to work exclusively within these limits to attain his goal.” Like Kracauer, Benjamin insists on a specular relationship between a retrospection of Chaplin’s film history and an “overview” of cinematic “possibilities” [Wirkungsmöglichkeiten]. And just as Kracauer’s emphasis in “Chaplin in Old Films” anticipates his other writings on historical redemption, so too does Benjamin here prefigure the historical excavations and citations that would come to dominate his intellectual labor in the thirties. The Circus is a key work for Benjamin because it registers film’s historicity, demonstrating a fracture between the now of the present and a visibly ancient if remembered past, a threshold across which Chaplin repeatedly trips throughout The Circus. Indeed, Chaplin is the filmmaker best equipped for this historical traversal precisely because of his simultaneous modernity and his spectral anachronism. The Tramp simultaneously evokes the engines and energies of industrial technology while resisting such progress through the deliberate anachronisms embedded in the Tramp’s attitudes and visual composition, which recall the faded fashions and leisurely gestures of the mid-nineteenth century metropolis. For Adorno, this ghostliness evokes both the former new medium of still photography as much as it does Kierkegaard’s “cityscape of 1840.” Similarly for Benjamin it is both Chaplin’s no less photographic observations of comic behavior during his London childhood and the still older model and vision of Dickens’ literature that explain the filmmaker’s parallax of centuries, technologies and cultures.

Stumbling between past and present much in the way he stumbled between competing discourses and desires amidst his various audiences, Chaplin, in The Circus, reveals the possibilities of a past lost but capable of fleeting re-capture. Indeed, the formulation that begins Benjamin’s essay, The Circus being at once “first product” and “product of old age” (the original is more direct: “Der ‘Zirkus’ ist das erste Alterswerk der Filmkunst.”), captures something of this non-chronological parallax, Chaplin’s importance being new only by virtue of being distinctly and recognizably old. This suddenly apparent distance, however, is not a cause for mourning, but rather offers both Chaplin and The Circus’s viewer an opportunity for both Rückblick and Überblick, measuring the present’s actualities in light of the possibilities inaugurated in the past, when cinema was once full of promise.

Beyond so many claims on Chaplin’s cinematic promise, Benjamin, Adorno and Kracauer emphasize first and foremost the Tramp as the figure of promise itself. Confusing tense and temporality, he reminds viewers not only what cinema was, but also what it might have been or, as importantly, what it still could be or become against history’s seeming necessities. If Chaplin was, for Kracauer, a fairytale prince fit for modern times, for Benjamin he would be in his comic stumbles “the only angel of peace for whom the earth has room” [Er ist der einzige Friedensengel, der auf die Erde paßt]. Drawn from one of his Denkbilder, this image simultaneously recalls a dream sequence of the Tramp as fallen gutter angel in The Kid (1921) and anticipates reference to Klee’s Angelus Novus in “On the Concept of History.” Yet in contrast to the latter, Chaplin’s angel finds peace rather than catastrophe on earth, doing so precisely as a figure of the past’s promises rather than their impossible resuscitation.

Such promise, however, is only visible if the views and reflections it occasions are collected, archived and shared. Chaplin’s own look back at his career in The Circus or Kracauer’s return to the filmmaker’s “old” comedies have as their pre-condition the preservation not only of films, but also of how these films were understood and appropriated by writers, critics and scholars. This is one reason why the publication of The Promise of Cinema is so important. Aside from offering a bounty of essential documents from a vital period in film history, Promise also presents a whole series of speculative, imaginary possibilities for the cinema that can and should not be relegated to the safe distance of a historical past preceding the now of our present. Rather, they should act on this present, exposing its historical contingency as well as uncanny commonalities or unseen differences between and across seemingly distinct periods in film history. Among the many political, artistic or philosophical promises Chaplin offered, perhaps most important was the promise of promise itself, one only visible because of the Tramp’s stumbles and looks in and out of time. It is not surprising that these would attract further retrospection on the part of so many German writers and critics (not to mention filmmakers like Ruttmann), but I would suggest that such redemption is no less at work in the montage that forms The Promise of Cinema. Approaching the “other possibilities,” “ghostly” images and seeming anachronisms spanning its pages, the contemporary reader has untold opportunities for summoning the promises dispersed across its pages. Chaplin is of course only one such specter. Others await their séance.

Download this article as a PDF.

Paul Flaig is Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of St Andrews. He has published widely on comedy, Weimar cinema, animation and media theory, including essays in Cinema Journal, Screen, Camera Obscura, animation, JCMS as well as several edited collections. He is co-editor of New Silent Cinema and is completing a monograph entitled Weimar Slapstick: American Eccentrics, German Grotesques and Hollywood Comedy Re-Functioned. He is co-director of the German Screen Studies Network.

Please cite this article as:

Flaig, Paul. “The Promise of Chaplin.” The Promise of Cinema. 18-05-2015. ./index.php/the-promise-of-chaplin/.