Note: For an optimal reading experience, please ensure your browser is rendering the page at 100% zoom ("Cmd/Ctrl +/-").

Fritz Lang, Sergei Eisenstein, and That Uncanny Mouse: The Work of Clues and Category Crises in M (1931)

ANNE NESBET

("Naturally nobody after so long a time can remember anything that might provide a trackable trace".")

--Fritz Lang, M (1931)

On every possible level, Fritz Lang's M (1931) is about trying to track things (and people), about trying to follow traces and find clues. That these "clues" lead sometimes in complicated or even category-confounding directions is what makes this film a puzzle that continues to unfold for the repeat viewer, many years and screenings after its premiere. Of all the many strange clues in Fritz Lang's M (1931), I would argue that one of the strangest is the sequence containing the "God's eye" shots of what seems to be a simply enormous compass inscribing circles on a huge map with a 3D model of a little garden house at its center. (This sequence runs from 17:07 to 17:54 here.)

We know that the garden house at the center of this image is a constructed, three-dimensional miniature because the previous shot took great pains to demonstrate that three-dimensionality, going as far as to position the camera at a dramatic angle so that we can clearly see the shadow of the compass ripple over the roof of the model as the pencil-end draws its great circle:

The function of this first shot of the giant compass and the map and the model is to make sure we understand the full scope of the strangeness of these images, their excessive deviation from "realism." To plop down onto a map a tiny built model of the set we have been shown two shots earlier (the set of the "Tatort," the "scene of the crime"), and then to add to that already jarringly complex image a gigantic "compass" to draw great circles around that built model, is to go to extraordinary lengths to make a visual point about the expanding scope of a criminal investigation.

The shots of the compass come in the middle of a sequence that is not only explicitly about tracing clues (specifically, to quote the voice-over here, any "verfolgbare Spur," or "trackable trace"), but that also, I will argue here, "expands the search area" of its investigation, (the voice-over explains when we are shown these images of the compass that "Mit jedem Tag erweitern wir das Fahndungsgebiet".), to include questions that would shock the investigators within the diegesis: what is life, what is a film, and who is telling this story? These questions, it turns out, lead us in short order to the figure of Mickey Mouse.

The shot following the compass shots—of a detective in a little candy store whose questions provoke only a shaking head and a look of perplexity from the woman behind the counter—uses both image and sound to perform its scene of investigative failure. The voice-over intones the sad state of affairs: ". . . natürlich kann sich Niemand nach so langer Zeit an irgend etwas erinnern, das eine verfolgbare Spur ergeben könnte . . ." ("naturally nobody after so long a time can remember anything that might provide a trackable trace"). And yet at the very moment the film raises the problem of memory (how does a film "remember"?), the image provides a substantial clue (unrecognized by the people within the diegesis) that points, as it were, toward two layers of the mystery at hand: not only the identity of the murder, but also the ontological puzzle presented by the film itself. Here is that image:

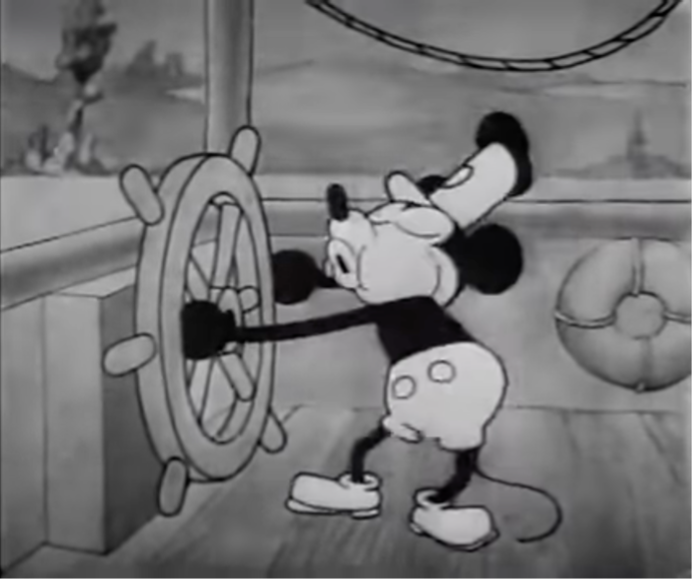

Centered between the two human beings who are (woman on the left) failing to remember and (man on the right) failing to find a trackable clue is a helpful, vivid creature, Mickey Mouse (pointing as pointedly as the compass, by the way) who is, in fact, the embodiment of a clue which the people here entirely overlook. What is the nature of this clue? On the simplest level, Mickey Mouse is displayed in this mise-en-scène (in triplicate, even) to remind us of a great recent (1930) hit in Berlin's movie theaters, Steamboat Willie (Disney, 1928).1 In Steamboat Willie, Disney's inaugural foray into synchronized soundtracks (and thus, in a sense, a natural companion for Fritz Lang's M, the director's first sound film), Mickey Mouse is introduced to us as he pilots a steamship while, famously, whistling.

Since in M the serial killer has a habit of breaking into a whistled version of "In the Hall of the Mountain King" at moments of excitement (and his whistle is what eventually allows the underworld to nab him), the reference here to Steamboat Willie should be seen as a big, generous hint. If only the police inspector in the candy shop (and the woman behind the counter) could pay a bit closer attention to the mise-en-scène within which they are embedded! Unfortunately, however, the people in this shot do not understand that they are "embedded within the mise-en-scène," and so they entirely overlook Mickey Mouse and everything he signifies here. They must overlook him; they cannot understand the clue represents, because, to be blunt, the clue is for us, the spectators who make up a kind of extra-diegetic investigative team.

Mickey Mouse in this image is not merely a clue; he is also the sign of a category crisis, a place where the diegetic and extra-diegetic worlds collide. There is something strangely excessive about Mickey Mouse, whose name, after all, doubles the "M" that is the visual hallmark of the film's own (extra-diegetic) title, as well as its (diegetic) chalk trace, slapped on the shoulder of the Murderer by one of the watchful, organized, detective-ized beggars. In this scene from the film Mickey Mouse precipitates a category crisis, which could be seen as an entirely appropriate role for him to play, he himself being the embodiment of a category crisis: what is this creature? Man or mouse? Inanimate drawing or living being? For that matter, what is the nature of any creature (actor or animation) who appears in a moving picture?

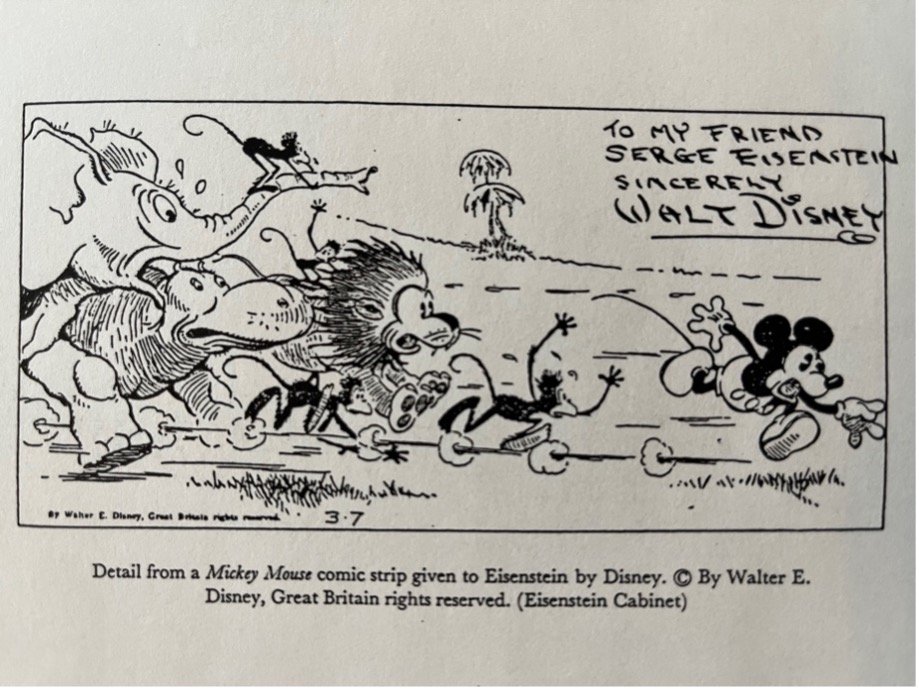

In the front pages of the edition of Eisenstein on Disney edited by Jay Leyda and published by Seagull Books in Calcutta in 1986, we find an image from a Mickey Mouse comic presented to Eisenstein by Walt Disney (it is inscribed, "To my friend Serge Eisenstein sincerely Walt Disney"): within a horizontal rectangular frame, Mickey Mouse runs toward the right edge, followed by a group of animals (elephant, hippo, lion, and four monkeys) who appear to be chasing him.2

The animals are separated from Mickey Mouse by a little bit of space and a great deal of ontological ambiguity. Mickey is not an "animal" the way that the animals chasing him are animals: he wears shoes, his little shorts, and white gloves. He is also angled a little toward us (whereas the animals race straight across the frame to the right), so that he appears slightly more three-dimensional than they do. He is thus "person-like" in certain key respects; we suspect he could talk if he wanted to.

This quality of Mickey Mouse—to be somehow in-between "animal" and "person"—is something that many thinkers interested in film wrestled with in the 1930s and 1940s. In 1932, Bernhard Diebold states confidently that Mickey Mouse, whatever he is, is not a "mouse":

Even if Mickey cannot be a "trained mouse"—because his "resemblance to humans" goes too far—Diebold does suggest that resemblance and mimicry must be part of the mystery: "Despite his mouse-like form, Mickey's expressions and gestures mimic those of a human being—or rather a human performer in the circus who is, for a few minutes, utterly removed from the serious concerns of life" (Diebold, 604). Mickey is then some "mouse-like" entity who can "mimic" the sort of human being already distanced from other, ordinary flesh-and-blood humans by being (thanks to make-up, comical movements, and other disguises) a "performer in a circus": Mickey exists in the realm of the in-between.

In some pages analyzing Disney's work that he wrote in 1940, Sergei Eisenstein also invokes the circus when he compares Mickey Mouse's ability to stretch his arms ("as he reaches up for a high note, the animated image of his hands disperses far beyond the limits of representation"4) to the feats of "boneless circus performers" (Eisenstein, Disney, 15). Where Mickey's stretched arms lead Eisenstein, however, is to "an ability which I would call 'plasmaticity'":

In both Eisenstein's and Diebold's accounts, Mickey Mouse's ambiguous positioning between "human" and "animal" suggests some sort of lesson about evolution: "primordial protoplasm, not yet having a stable form," for Eisenstein; a stage in which humanity (or at least circus clowns) can be mimicked, though not yet achieved, for Diebold. In a note from 1931, Walter Benjamin takes the evolutionary analysis of Mickey Mouse in a different direction by proposing a post-human explanation for Mickey's weirdness: "Mickey Mouse proves that a creature can still survive even when it has thrown off all resemblance to a human being. He disrupts the entire hierarchy of creatures that is supposed to culminate in mankind."5 For all of these thinkers, Mickey Mouse provides a snapshot of evolution in the middle of its work—a creature on its way to being something new, appealing because of its combination of the familiar and the unfamiliar.

Fritz Lang's film M, by the way, is also a "creature on its way to being something new," a transitional object in cinema's evolution from silence to sound. Although sound certainly deepens the resonance of each image in the opening scenes of M, those shots use the visual vocabulary of a late silent film, and in fact the prologue "works" as a silent film, if we imagine the subtitles playing the role of mock intertitles: the camera shows us the children's counting-off game from slightly above, pivots to follow the woman with the laundry basket; we watch her climb the stairs; we see various people interact with Elsie's waiting, anxious mother; we have inserts of the cuckoo clock, to remind us of time passing, and at the end of the prologue we are shown telling, rather beautifully organized images of the empty place at the table, set for the missing girl, the geometrically symmetrical (empty) staircase, the ball rolling out from a bush, the balloon-creature caught in the wires. All of this works better with sound (the heavy footfall of the woman carrying the laundry basket up the stairs, the desperate call of "Elsie!" ringing through those shots of places-where-Elsie-is-not), but it still makes sense without sound. By the end of the film, however, everything is different. By the time Peter Lorre delivers his desperate, impassioned, lengthy monologue in the last fifteen minutes of the movie, M is no longer conceivable as a "silent film." Much of M's appeal—and of its power—comes from the way it explores, formally, the meaning and potential of the transition from silence to sound, understood as a kind of category crisis.

The character of Mickey Mouse is a transitional figure in another respect, as well, oddly situated as he is between charm and fear. "Omni-appealing" says Eisenstein of Disney—but also, "[s]ometimes it's frightening for me to watch his works . . . . His creation comes from somewhere near the zone of the purest, most primary depths" (Eisenstein, Disney, p. 37).6 Benjamin in 1931 explains that "[a]ll Mickey Mouse films are founded on the motif of leaving home in order to learn what fear is" (Benjamin, "Mickey Mouse," 403).

Both familiar and unfamiliar, both "omni-appealing" and potentially frightening, Mickey Mouse embodies (ambiguously, since his very body is by nature ambiguous) Freud's category of the uncanny ("das Unheimliche"), "that class of the terrifying that leads back to something long known to us, once very familiar."7 Mickey Mouse, in this sense, is also by nature a clue, apparently leading somewhere. A clue, understood as a symptom: Schelling (cited by Freud) claims that "everything is uncanny that ought to have remained hidden and secret and yet comes to light" (Freud, 376).

Freud kicks off his own analysis of the uncanny with a close look at the German words "heimlich" and "unheimlich"; he discovers an already uncanny relationship between the two, since "[w]hat is heimlich thus comes to be unheimlich" (Freud, p. 375). Interestingly, one of his first examples is the question of what heimlich means when applied to animals: "tame, companionable to man. As opposed to wild, e.g. 'Wild animals . . . that are trained to be heimlich and accustomed to men'" (Freud, pp. 371-372). Whether Mickey Mouse can be considered a "tame" mouse is a question that throws us into the category crisis all over again: for one thing, mice (as animals) have a longer history of being considered an infestation than as "companionable." But it is also true that Mickey's anthropomorphic qualities do not exactly make him appear "tame"; they suggest, instead, a creature who has almost human-like agency, who commands more than he obeys (and Mickey's disobedient side is often uppermost). At the same time, poised as he is on some evolutionary cusp close to "man," Mickey Mouse doesn't fit comfortably into the "wild" category, either. This category crisis indeed is part of what endears him to his audiences, as Benjamin asserts: "[T]he explanation for the huge popularity of these films is not mechanization, their form; nor is it a misunderstanding. It is simply the fact that the public recognizes its own life in them" (Benjamin, "Mickey Mouse," 403). The strangeness of Mickey Mouse is uncannily combined with an aura of profound familiarity.

Indeed, Freud's discussion of the uncanny reminds us how we are, as human beings, in certain respects uncannily like Mickey Mouse, perhaps particularly in how we feel ourselves to be in some kind of evolutionary transitional phase:

Eisenstein echoes this argument in notes on Disney from 1940: "And at the center of it all, even with Disney, stands Man. But Man, seen as if in reverse in his earliest stages, which were sketched out by . . . Darwin" (Eisenstein, Disney, 11). The question of Mickey's ties to animism is certainly uppermost in Eisenstein's mind as he explores the power of Disney's work. We have discussed some of the category crises triggered by Mickey Mouse ("mouse" or "man"? "tame" or "wild"?), but the most pressing dilemma is presented by that question of animation: what does it mean to be animated? Is Mickey Mouse "alive" or "mechanical" or somewhere strangely in between the two? In the "Uncanny" essay, Freud cites Jentsch's definition: "doubts whether an apparently animate being is really alive" (Freud, p. 378). Eisenstein points out that "The very idea, if you will, of an animated cartoon [animation: literally, a drawing brought to life] is practically a direct manifestation of the method of animism" (Eisenstein, Disney, 33):

In this way, what Disney does is connected with one of the deepest features of the early human psyche. (Eisenstein, Disney, 33)

The uncanny nature of animation, for Eisenstein, is the way it confronts us with yet another category crisis: the split between what we "know" and what we "sense" (or "feel"):

We know that this is a projection of drawings onto a screen.

We know that they are "miracles" and tricks of technology and that such beings don't actually exist in the world.

And at the very same time:

We sense them as living,

We sense them as active, acting,

We sense them as existing and we assume that they are even sentient! (Eisenstein, Disney, 52 [note dated 1941])

It is not just animated characters who can be two things at once. Eisenstein's favorite example—which he brings up in a number of different writings, and which scandalized the audience when he included it in his lecture to the All-Union Congress of Soviet Cinema Workers in 1935—is one he got from Levi-Bruhl, that of the Bororo Indians from northern Brazil, who "claim that they, being humans, are simultaneously a particular type of red parrot common to Brazil."8 This simultaneity of contradictory identities is something Eisenstein sees at work in Disney's animations:

To the conscious logical mind, the form of the Bororo is unfathomable, obviously operating in a sensuous mindset—here, in Disney's parrot, it is tactile, active, and of course entirely capable of submerging into the depths of a sharply sensuous mode of thought. (Eisenstein, Disney, 50. [note dated 1941], emphasis mine)

Which of Disney's parrots is Eisenstein referring to in this quote? There are two likely possibilities (and in both the parrot co-stars with Mickey Mouse): Mickey's Parrot (1938) and Steamboat Willie (1928). In Steamboat Willie, the parrot has the only spoken words in the film: "Hope y'don't feel hurt, big boy," (and, later, "man overboard") which it indeed parrots rather mechanically.

(Let's note that the unsettling effect of mechanical language, here given to a parrot, is also a big part of what makes the opening scene of M so chilling: that ring of children in a clock-like formation, filmed from one side and above, listening as a girl chants—mechanically—a sinister counting-out rhyme about murder. The multi-layered clash between the child's appearance, the mechanical chant, and the girl's grisly words creates a sense of ambiguous darkness right at the start of the film.)

Even though the parrot in Steamboat Willie can talk, it is not coded "human" to the degree that Mickey and Minnie are: the mice may be unspeaking, but they wear basic clothing and display a certain degree of creative agency (playing the drums, turning a goat into a music box). But since in Eisenstein's Disney writings of the early 1940s, there is an explicit reference (Eisenstein, Disney, 31) to another Mickey Mouse cartoon from the late 1930s, Hawaiian Holiday (1937), about which we will have more to say in a moment, I suspect that when Eisenstein refers to "Disney's parrot" in 1941, he is most likely speaking not of Steamboat Willie, but of Mickey's Parrot (1938), although both of these Mickey-related parrots are interesting creatures for what they tell us about the conundrum of animation.

In Mickey's Parrot (1938), Pluto (Mickey's dog, performing the role of a non-speaking "animal") and Mickey Mouse (here the "person" in the Mickey/Pluto duo) spend some anxious time thinking their house is being taken over by a vicious killer, when the creature doing the haunting is actually a parrot accidentally dropped off the back of a truck one stormy night right by Mickey Mouse's mailbox (the mailbox being the first sign of Mickey's "personhood" in this film). Inside the house, Mickey (in pajamas and in bed) and Pluto (dressed only in his dog collar and on his dog bed) are shocked to hear a "News Flash" on the radio about an escaped criminal. Both are terrified; Mickey grabs his rifle; and the poor parrot (chirping "ship ahoy!") accidentally slides down the coal chute into the basement, making enough noise to terrify Mickey and Pluto upstairs. Then follows a series of gags in which the parrot uses his repertoire of phrases and/or his ability to move to "animate" various objects and creatures, including a fish in a fishbowl and (in the most stunning gag of all) a dead, plucked chicken, who is made to walk and talk, to Pluto's evident terror.

A bird animating a dead bird is a rather dark version of the kind of ecstatic visual joke for which Eisenstein had a real fondness (like the example Eisenstein took from another Mickey Mouse film of a swarm of tiny mosquitoes forming themselves into the image of one huge "mosquito," an example cited by Dustin Condren in his recent book on Eisenstein9). The recursive nature of the gag—since the "living" parrot inside the dead chicken is himself only an animated creature, a drawing-based puppet—suggests a kinship with a broader category that always fascinated Eisenstein: the pars pro toto, the relationship between part and whole, and particularly those instances where the part embodies something essential about the nature of the whole. Eisenstein is delighted by the ability of animation to create striking instances of pars pro toto; he mentions specifically (in a Disney note dated 1940) Mickey Mouse's tour de force in Hawaiian Holiday (1937), in which Mickey's fingers, playing the ukulele, turn into the limbs of people dancing to the very music he/they are playing: "The two middle fingers become legs and the two fingers on either side become little arms. The second hand becomes the partner. And now it's no longer two hands, but two funny little white men dancing elegantly along the ukulele strings." (Eisenstein, Disney, 31)

By "animating" a part of a previously animated whole, this eminently recursive gag calls into question the illusion of "life" that animation provides: what does it mean to "animate" something that already seems to be "alive"? Doesn't such subsidiary animation actually make the "whole" seem somehow, in retrospect, less alive? (A similarly uncanny effect, by the way, can be achieved by subjecting a living actor to stop motion animation.10)

Disney's parrots—and especially Mickey's Parrot—lay bare the device of animation in two respects: they remind us of the leap of faith we take when assume that apparent motion should be read as "life," and they remind us of the power of a synchronized soundtrack to create an uncanny whole. Both Steamboat Willie's relatively primitive parrot, who has only one verbal phrase, and the quite advanced parrot of Mickey's Parrot, who knows many phrases but speaks them in a decidedly parrot-like manner (as rote expressions whose elements are fixed groups of words), subtract a certain amount of human-ness from the nature of language and make the relationship between word and image several degrees more mechanical. In Steamboat Willie, a film showcasing the innovation of the synchronized soundtrack, the parrot's line has the distinction of being the only part of that soundtrack formed not from noise or music, but from words. In Mickey's Parrot, the parrot's slightly mechanistic speech demonstrates the power of a soundtrack to be perceived by its gullible spectator (in this case, our within-the-diegesis canine representative, Pluto) as integrally, organically linked to the images and movements of objects and creatures that spectator sees, even when in fact that linkage is only an artificially constructed illusion.

The connection between sound and image is what leads Bernhard Diebold to claim in 1932 that Mickey Mouse "is an initial example, a mere template for a potentially great art of film" (Diebold, 606). For Diebold, that "potentially great art" toward which Mickey is pointing is "an absolute animated film that would represent the tonal ornaments of music through visible and graphic ornaments of the moving film," and he cites the experiments of Ruttmann and Fischinger as early examples (Diebold, 606). It is via Mickey Mouse, however, that he comes to his proposed term for this new artistic achievement:

Taking the hidden evolutionary link into account, however, we could indeed call this goal not merely musographics, but mouseographics [Mausographik]. The animated Mickey Mouse—himself profoundly "in between" human and animal, living creature and mechanical puppet—here points us toward a future abstract cinema. We might even say: he haunts it in advance.

Mickey Mouse as a signal for a future cinema—or as first symptom of a future human relationship with cinema—can also be found playing a role in Walter Benjamin's theoretical writings. As Miriam Bratu Hansen points out in her analysis of an early (1936) version of Benjamin's "The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility" (famous in its third incarnation, dating from 1939), the section on "the optical unconscious" was "originally entitled 'Micky-Maus'" and in it "Benjamin tries to make a case for film as the form of play that could at the very least neutralize, on a mass basis, the traumatic effect of the bungled reception of technology."11 Mickey Mouse, as a "figure of collective dream," can help, by inspiring "collective laughter," to provoke a "preemptive and therapeutic eruption of such mass psychoses."12 Benjamin calls this effect "psychic immunization [Impfung]," and as Hansen explains, this "immunization" works by means of the synchronization of sound and image (what we playfully termed above, following Diebold, "mouseographics"): "The films provoke this laughter not only with their 'grotesque' actions, their metamorphic games with animate and inanimate, human and mechanical traits, but also with their precise rhythmic matching of acoustic and visual movement" (Hansen, 2004). Note that in this list of characteristics, we find the synchronized soundtrack taking its place next to other more traditional aspects of the uncanny (tensions between animate/inanimate and human/mechanical).

We have already seen the uncanny aspects of synchronization laid bare in Mickey's Parrot (1938). But a very similar uncanniness of the relationship between sound and image is one of the most powerful devices powering Fritz Lang's M, the focus of our discussion here. In the sequence of M described above (the one that guides us from police detectives to a giant compass to Mickey Mouse's cameo appearance), uncanny effects are produced by the innovative way the voice-over becomes a soundtrack guide for the images that is as precisely synchronized as the music of a Mickey Mouse cartoon. Let's return to that sequence now, paying close attention to the way the soundtrack and the image track interact.

The diegetic justification for the voice-over in this section of the film is given in shots where the police inspector is speaking about the (as yet unsuccessful) search for the serial killer to an impatient government official on the telephone. Over the course of a few shots, the diegetic telephone conversation evolves into a voice-over that functions like the soundtrack for a Disney Silly Symphony—a soundtrack made from spoken text, however, instead of music. At first the voice-over functions like that of a nature documentary—the police officer's voice describes how tired his men are, and we are shown a shot of tired policemen yawning and reclining on benches in the police station. There may even be a bit of an ironic tension between the voice-over's urgent discussion of how hard such a frustrating investigation is on the men involved, how they never go home anymore: we see men sitting at a table in the station, but their tired consumption of some liquor is at odds with the urgent tone of the voice-over. By the following shot, however, there is a further evolution of the relationship between sound and image. In this shot—in which we are introduced to the garden hut described to us as the "Tatort," the scene of the crime—the words of the voice-over are synced as precisely to the image as the sounds of Steamboat Willie to the images of Mickey Mouse pounding on makeshift drums or whistling. The voice-over says, "Bedenken, Herr Minister, allein die Arbeit am Tatort. Da wird, zum Beispiel, dahinter einem [pause] Zaun, in einem Gebüsch, eine kleine, weiße, zerknüllte Papiertüte gefunden" ("Consider, Mr. Minister, the work at the scene of the crime. There, for instance, behind a [pause] fence, in a bush, we find a small, white, crumpled-up paper bag," emphasis mine). The words "fence" and "bush" are precisely synchronized with the movements of one of the police inspectors in the frame, who touches each of those objects at the very moment its name is mentioned in the voice-over. As the voice continues the description of the investigation of the little paper bag, a close-up image helps us follow along; when the voice-over mentions crumbs in the corner of the bag, we see those crumbs and that corner. All of this marks the voice-over's new role as synchronized, Disneyesque soundtrack.

The synchronized soundtrack (here with the words of the voice-over playing the role of the music and sound effects in Steamboat Willie) has an uncanny effect on the spectator because it emphasizes the nature of the film as an artificially constructed, made object. This unsettling synchronization has an "animating" (and at the same time dehumanizing) effect on the live-action actors in the shot. The category crisis expands to infect not merely the characters but even the spectators, who, finding themselves engaging with a pointedly constructed object, must naturally begin to ask: where is the maker of this object?

I think that is very much the point of the following two shots, which are the shots of the gigantic compass with which we started this essay. The image of the compass, the map, the little 3D model of the "scene of the crime" set finally take us entirely out of the "seemingly real world" (a removal from the illusion of natural life that the too-perfectly synchronized voice-over had already set up). But let's consider once more the second of those compass shots: after the voice-over closes out the first of the compass shots with "Mit jedem Tag erweitern wir das Fahndungsgebiet" ("with every day we widen the search area"), the image shifts to a view from just about directly above of the compass, with the little model of the Tatort now centered in the map below. I think there is something of a visual joke being made here, in the very blurring of the top of the compass as the shot progresses:

The compass, I submit, is operating a little here like the Tower of Babel, stretching up toward the place where the "maker" of the film resides, that being that can make images and soundtrack voice-over so exactly coincide. The compass thus indeed "widens the area of the search" by beginning to reach toward that extra-diegetic realm (where the "maker" and "making" are located) to which we cannot actually have access from within the art object. The blurring of the top of the compass reminds us that the compass points (in its vertical axis) to what cannot be seen: the wielder of the compass, the maker of the film. The blurring of the compass may function here like the blind spot in the eye (from whence the optic nerve travels from eye to brain) or the "navel" of the dream, as described by Freud in his Interpretation of Dreams (1899).13

And now we understand better the uncanny nature of Mickey's clue in the following shot (the extra-diegetic reference to the whistling theme of Steamboat Willie as a sign of the diegetic whistling of the killer): as a gesture to us as spectators, awkwardly in between the world outside-of-the-film and the world within the diegesis. Mickey Mouse's clue points (as the compass pointed in the previous shot) to the world of M as a constructed story, something with a maker, or, to use Diebold's terms, the "fully sovereign genius" that "great art demands": "one who forms the elements of the film single-handedly, as does the creator of Mickey Mouse" (Diebold, p. 605). Interestingly, Diebold draws an important distinction between the animator (for example, "the creator of Mickey Mouse") and the film director, who, he claims, just rearranges things; the director is "not an artist of the first order" (Diebold, p. 605) Fritz Lang's M provides a counter-argument in this sequence, in which the director reveals himself to be, at heart, an uncanny maker and animator of a constructed cinematic world. In other words, the film becomes uncanny as it shows us what we cannot see.

This function of cinema—showing us what we cannot see (in two senses: both showing us what we cannot usually see with our eyes and, at the same time, making "visible" to us the fact that there are always things we are not able to see, with whatever apparatus we are currently seeing)—is what Walter Benjamin is wrestling with in the section of the Artwork essay originally devoted to Mickey Mouse. The subject there is the "optical unconscious," the way that "slow motion" can uncover for us aspects of movement of which we had no idea and the "close up" can reveal worlds we did not know exist: "So wird handgreiflich, daß es eine andere Natur ist, die zu der Kamera, als die zum Auge spricht" ("Thus it becomes tangible that there is a different nature that speaks to the camera than that which speaks to the eye").14 Indeed, as M repeatedly informs us, the world is simultaneously playing to many different kinds of eyes—to the "eyes" of the characters within the diegesis, to the camera's "eye," to our own spectatorial eyes. The clue that Mickey Mouse provides in M is invisible for the characters, even though carefully centered for us, the spectators. But the very existence of something (like this Mickey Mouse) that only certain eyes can "see" or understand reminds us of the limits set on our vision and everything else that we cannot see. Who, for instance, plants this Mickey clue for us to understand? We can follow the compass/Tower of Babel toward the maker (Diebold's "sovereign artist") only a little part of the way—and then our vision blurs. We can think of the experience of the uncanny as the experience of being drawn into some kind of diegesis, becoming, eerily, part of the story. The "world" seems to reveal its nature as a constructed, made thing. This effect—in Mickey Mouse cartoons as in Fritz Lang's M—can be produced in a number of ways (a synchronized soundtrack, a shot with some absurd combination of model and map that forces us to ponder its making, a reference to something the characters, trapped in their "world," cannot understand), but in each case it teaches us at one and the same time to see in a new way—and to acknowledge that there are uncanny limits set, always, on what we are able to see. Part of the genius of M is the way it unsettles us by showing how even we spectators are tangled up in the category crises it foregrounds and reveals.

Footnotes

1 Disney's Mickey Mouse films began to be screened in Berlin in early 1930. See Jörg-Peter Storm, Mario Dreßler: Im Reiche der Micky Maus (Dokumentation zur Ausstellung – Walt Disney in Deutschland 1927–1945 – im Filmmuseum Potsdam). Berlin 1991.

2 Frontispiece, Eisenstein on Disney, ed. Jay Leyda, trans. Alan Upchurch (Calcutta: Seagull Books, 1986), p. vi.

3 Bernhard Diebold, "The Future of Mickey Mouse (Theory of Animation as a New Cinema Art)" [1932], trans. Michael Cowan, in The Promise of Cinema: German Film Theory, 1907-1933, ed. Anton Kaes, Nichoas Baer, Michael Cowan (Oakland, California: The University of California Press, 2016), pp. 603-607; this quote p. 605.

4 Sergei Eisenstein, Disney [this note dated 1940], ed. Oksana Bulgakowa and Dietmar Hochmuth, trans. Dustin Condren (Berlin: PotemkinPress, 2011), p. 12.

5 Walter Benjamin, "Mickey Mouse" ["Zu Micky-Maus," 1931], trans. Rodney Livingstone, in The Promise of Cinema: German Film Theory, 1907-1933, ed. Anton Kaes, Nichoas Baer, Michael Cowan (Oakland, California: The University of California Press, 2016), p. 403.

6 Although the Russian translation of "unheimlich" as "zhutkoe" erases the paradoxical and hidden "familiar" side of the German term, Eisenstein was not limited to Russian sources.

7 Sigmund Freud, "The 'Uncanny'" [1919], trans. Alix Strachey, in Collected Papers, Volume IV (London: The Hogarth Press, 1950), 368-407; this quote 369-370.

8 Eisenstein, Disney, p. 47. The editors' footnote gives the original citation for this passage quoted by Eisenstein: Levi-Bruhl's book Primitivnoe myshleniie (Moscow: Ateist, 1930).

9 Dustin Condren, An Imaginary Cinema: Sergei Eisenstein and the Unrealized Film (Ithaca: Cornell UP, 2024), p. 273. Condren points out that the source of this image of a meta-mosquito is almost certainly Disney's 1934 Mickey Mouse film, Camping Out.

10 See Jan Švankmajer's decidedly uncanny take on Alice in Wonderland: Alice (1988).

11 Miriam Bratu-Hansen, "Room-for-Play: Benjamin's Gamble with Cinema," October, Summer 2004, Vol. 109, pp. 3-45. This quote p. 29.

12 Walter Benjamin, Selected Works, Vol. 3, p. 118, as cited in Bratu-Hansen, p. 29.

13 As Freud says in a footnote: "There is at least one spot in every dream at which it is unplumbable—a navel, as it were, that is its point of contact with the unknown." Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams [Traumdeutung, 1899], trans. James Strechey (New York: Avon, 1965), p. 143.

14 Walter Benjamin, "Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit (Erste Fassung)," Gesammelte Schriften, I-2, ed. Rolf Tiedemann and Hermann Schweppenhäuser, (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1991), 435-469; this quote p. 461.