Note: For an optimal reading experience, please ensure your browser is rendering the page at 100% zoom ("Cmd/Ctrl +/-").

Amateurs: Rethinking Menschen am Sonntag

Noah Isenberg

Shot on the eve of the Great Depression, with essentially no budget to speak of, an equally modest cast of amateur actors, a relatively untested, unknown crew, and no major studio backing, the late silent film Menschen am Sonntag (People on Sunday) has a production history like no other. After the more seasoned director Rochus Gliese abruptly abandoned the project, merely a few days into the shoot, the picture was co-directed by two budding filmmakers in their twenties, Robert Siodmak, twenty-eight, and Edgar G. Ulmer, twenty-four, neither of whom had ever made a feature film. It was more or less scripted, though not in any formal sense, by a boyish Billy (then still "Billie") Wilder, twenty-three, with story input from Curt (then still "Kurt) Siodmak, twenty-six. The camera was operated by veteran special effects technician Eugen Schüfftan, the old man of the bunch at thirty-six with assistance from Fred Zinnemann, twenty-two, and the project was produced by the coffeehouse collective Filmstudio 1929, a one-off production company cobbled together by crewmembers and theater impresario Moriz Seeler, with nominal support from Nero-Film boss, and maternal uncle to the Siodmak brothers, Heinrich Nebenzahl.

Almost every person originally associated with the film—in particular, Ulmer, the Siodmak brothers, and Billy Wilder—would later, after migration to Hollywood and after the film's cultural cachet had accrued over time, take more credit for the film than the record allows. In an interview in 1970, for example, Robert Siodmak effectively denied Wilder's involvement, insisting that he worked no more than an hour on the production—his sole idea, in Siodmak's recollection, was that Annie, the model-girlfriend in the film, should stay home in bed—and claimed that Ulmer, after eight days on the shoot, returned to America. He asserted, moreover, that Ulmer really only worked one day. "On the first day," remembers Siodmak, "he wanted to take the thing away from me." Retrospective accounts of this kind differ quite radically, even those told by the same person. In Siodmak's posthumously published memoir, Zwischen Berlin und Hollywood (Between Berlin and Hollywood, 1980), for instance, he refers to Ulmer as his "co-director" and maintains that he had his true interests at heart.

For his part, Ulmer, who claims to have "organized" the entire production, and to have bankrolled it with money brought from the United States, remembered it as a truly collaborative undertaking: "Our main weapon was that everyone could contribute his bit; even the assistant Zinnemann was allowed to participate in the discussion." Many years later, in Gerald Koll's documentary on the making of the film, Weekend am Wannsee (Weekend at the Wannsee, 2000), Brigitte Borchert, who plays the girl from the Electrola shop, remarks, with perhaps less of a personal stake: "They didn't have a script or anything . . . We'd sit at a nearby table while they'd decide what to do that day . . . It was completely improvised." By her account, Wilder's main function during the shoot was to hold a sun reflector.

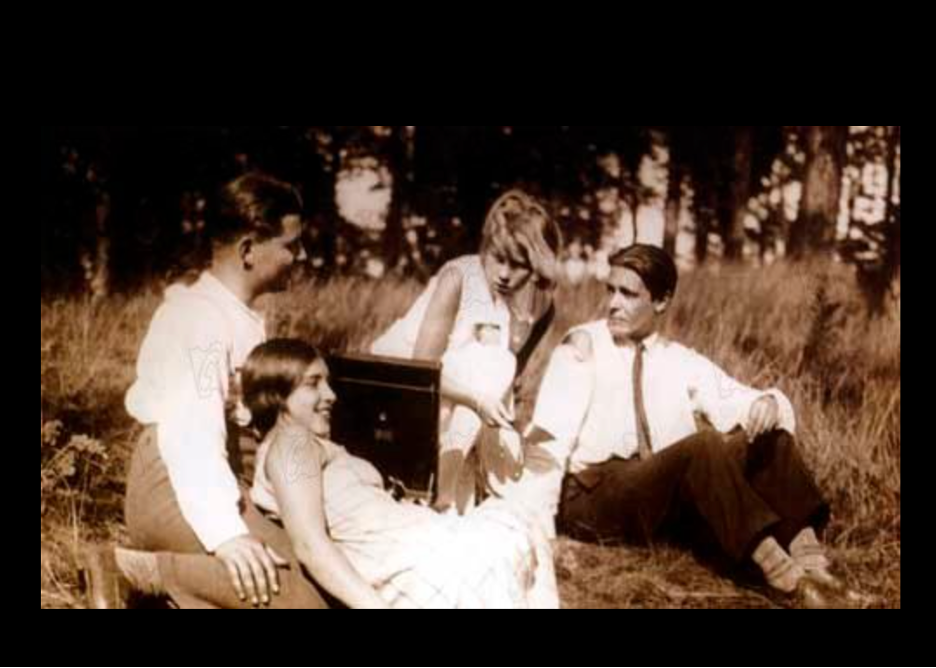

Contemporary journalistic accounts of the shoot add a few critical details taken from the public record and offer further testimony as to the question of who was actually involved. During the early weeks of production, in July 1929, a pair of articles published in Weimar Berlin's popular press reported on the unconventional character of the work—its programmatic working title was "So ist es und nicht anders" ("This is How it Is, and No Different")—offering, much like a press kit would do, short profiles of the cast and crew. In the Filmspiegel supplement of the Berliner Tageblatt on July 25th 1929, Delia Arnd-Steinitz discusses the initial screen tests at Berlin's Thielplatz, not far from the Grunewald forest, and the revolutionary decision on the part of the newly established Filmstudio 1929 (she names Seeler, Ulmer, and Robert Siodmak as its founders) to use amateurs as a means of expressing real-life authenticity. "The plot," she writes, "should come as close as possible to reality, to the natural course of our days; the events, moods, and conflicts of everyday life should be represented without kitsch, pathos, or sentimentality." Accompanying the article are several photos from the ongoing production, one of which shows Ulmer, together with Siodmak, Gliese (still present there in the early days of the shoot) and Seeler, taking the screen test of two of the film's amateur actors Christl Ehlers and Erwin Splettstößer.

Five days later, in another article published in the afternoon edition of the Berliner Zeitung, the cultural reporter Pem (a.k.a. Paul Erich Marcus, a regular at the Romanisches Café, where the project was allegedly first hatched), filed a dispatch, "Film mit Dilettanten" ("Film with Dilettantes"), on the next phase of shooting on location at the Nikolassee train station and at the surrounding beaches and forests of Wannsee and Grunewald. In it, he provides an overview of the film crew, often misspelling or mistaking their names altogether, and giving a cheeky summary of their professional background: "Script: Billie Wider [sic], coffeehouse-born journalist and gagman . . . Direction: Rochus Gliese, actually a set designer, but he doesn't need to design the Grunewald. . . .Set professional and jack-of-all-trades: Fred [sic!] Ulmer, a fiery business fiend [Betriebshasser] and Hollywood-studio connoisseur." Such descriptions, while meant more as humorous caricatures than professional bona fides, are revealing nonetheless; alone the juxtaposition in Pem's portrayal of Ulmer as having both a strong anti-establishment attitude and the insight of someone who had already amassed experience working in Hollywood is illuminating. Finally, in the same article, the accompanying photo from the shoot on location shows Seeler, Schüfftan and Ulmer, all of them identified in the caption, huddled around a camera in the middle of the forest. "Here something is evolving," writes Pem, commenting on the transitional and possibly transformative quality of the project, "which can only be thought of as an experiment, a mere signpost; and that's already saying something in our schematized and calibrated age in which technology has grown at a rate over life."

In terms of its formal innovation, People on Sunday takes the city symphony film, commonly associated with Walter Ruttmann's Berlin: Sinfonie der Großstadt—and, in the international arena, with Alberto Calvacanti's Rien que les heures (1926) and Dziga Vertov's Man with a Movie Camera (1929), among others—in a new direction. Unconcerned with merely capturing a "Querschnitt," or cross-section, of the German metropolis, the film cannily blends avant-garde documentary and narrative cinema into something that is less abstract, far more improvised, natural, and overtly romantic than its predecessors. While it draws in part on the once dominant trend of Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), with its periodic riffs on popular advertising, design, photography and technology—and, more generally, on the wider contemporaneous trend in Europe and America of capturing the pulsating life of a city on celluloid—its main conceit is its utter defiance of prevailing modes and industry norms. The film turns its back on studio production, instead allowing the city and its many inviting locations (its boulevards and cafes, lakes, boardwalks, beaches, and other places of leisure and recreation) to substitute for the standard reliance on sets, while at the same time allowing amateurs to play the roles otherwise reserved for film stars. It is, as we are told at the outset, "a film without actors."

The premise of the film couldn't be more basic: in the heart of the city, near the Bahnhof-Zoo subway station, amid the intense bustle of commerce and traffic, a modern boy-meets-girl story seems to be transpiring before our eyes. A chance encounter between two young, slightly aimless urban strollers results in an impromptu scheme for a Sunday outing, which, after each one shows up with a best friend in tow, becomes a frolicsome double date at one of Berlin's nearby lakes; the fifth member of the cast, in a witty twist attributed to Wilder, oversleeps the entire outing. What ultimately unfolds in just a little over an hour of total screen time is a remarkably straightforward depiction, by turns affectionate and comical, tender and gruff, of courting rituals, leisure activity, and mass entertainment circa 1930. We see the four protagonists listening to music, swimming, enjoying a picnic, riding a pedal boat, alternating their love interests, and trying in general to squeeze the most out of the day. The style of the film is natural, the setting unpretentious, and the atmosphere, perhaps the core of the entire film, shamelessly flirtatious. More than anything, a new kind of directness, an unmediated, unvarnished representation of everyday life as it is experienced by members of a young, urban consumer class is what the filmmakers seem to have been after, in marked contrast to the big-budget spectacles being produced at Ufa at the time. Among the working titles, in addition to "So ist es und nicht anders" were those of a universal appeal, "Sommer 29" ("Summer '29") and "Junge Leute wie alle" ("Young People like Us"), a wink at the film's critics and its target audience.

By casting amateurs in roles based on their true day jobs and with their real names still attached to them, all from the minor professions of a burgeoning young, urban work force, the film crew was able to offer an unusually honest, verité rendering of their world, to an audience that was preoccupied with the same values, social mores, dreams and anxieties as the protagonists on the screen. In the opening credits, following the initial announcement made via intertitle that the film's five lead characters appear here before the camera for the first time and are today back at their old jobs, we are immediately introduced to them in their respective pursuits: the jovial taxi driver Erwin Splettstößer, seated behind the wheel of a cab bearing the Berlin license plate "IA 10088"; the charming record salesgirl Brigitte Borchert in front of the Electrola shop on Kurfürstendamm—where Moriz Seeler is said to have discovered her—who last month, so the title reads, sold 150 copies of the hit song "In einer kleinen Konditorei" ("In a little Pastry Shop"); the tall, dark and slender Wolfgang von Waltershausen, a former officer, farmer, antique dealer and gigolo, currently working as a traveling wine merchant, puffing on his cigarette with an air of obvious self-assuredness; the very chic, urbane Christl Ehlers, who enters what appears to be a casting studio, and who, we are told, "wears down her heels as a film extra"; and, finally, Annie Schreyer, a model, reclining, filing her nails, and waiting in vain for the next job.

In a manner not unlike the early Soviet avant-garde—Ulmer claims to have taken the chief inspiration from Vertov—the film has its characters serve as a series of social types, easily recognizable by the audience. Writing in Weimar Germany's Communist Party newspaper, Die rote Fahne, critic Alfred Kemeny extolled the fact that the film evolved "outside the German capitalist film industry" and underscored the influence of Russian cinema: "the plot is plain, as if simply carved out of life, and that here, as in the Russian films, human beings, real, real, real [sic] human beings 'play' [their true roles]." The film's five leads participate actively in forming the very mass culture that they represent on screen, a culture with which Weimar-era cinemagoers readily identified. Writing in Tempo in late July 1929, when the production was in full swing, Wilder drew further attention to the contrast between their independent enterprise and big-budget films made at Ufa. "A few miles down the road," he observed, "on the premises of Neubabelsberg, they may at this very moment be tearing apart the monumental sets for Nina Petrovna's 'wonderful lies' [i.e., Die wunderbare Lüge der Nina Petrovna (The Wonderful Lies of Nina Petrovna, 1929)] while we are busy shooting a few truths we consider important, for a laughably small sum of money."

"The five people in this film," remarked Wilder further in the same piece, "that's you and me." Admittedly, the film's primary viewpoint, with its occasional flourishes of voyeurism, its unabashed prankster sensibility and boyish bravado, is quite masculine and, especially from today's vantage point, even predatory in certain scenes. The audience serves, in part, as witness to Wolfgang and Erwin's youthful exploits: their fraternal bonds, from their chummy card game near the start of the film to their final splitting of a last cigarette, are shown to run deep. Yet the leading women, whose roles shift and evolve throughout the picture, are not without their share of complexity and individual force. Indeed, they challenge their male counterparts, undoing their immature schemes and standing their own ground.

By dint of good fortune, or perhaps good connections, the film enjoyed a well-publicized premiere at the glamorous Ufa-Theater am Kurfürstendamm on February 4, 1930—the elegant letter-press invitations list the official credits: script by Wilder, cinematography by Schüfftan, direction by Siodmak and Ulmer—and was instantly embraced by critics from nearly all the city's leading newspapers. In a cloud of media euphoria, they pronounced it "a grand success," "magnificent," and "a delightful film." One review, which declared the victory of the low-budget Filmstudio 1929 (it lists the total cost of production at 28,000 Reichsmark or the rough equivalent of $7,000 at the time) over the powerful entertainment industry, hailed the film in similarly effusive terms: "A triumph of the artistic element—proof that it works this way as well—a film made from crystal-clear simplicity." The unnamed reviewer then goes on to note, underscoring the film's universal appeal: "Nothing actually happens and yet it still captures that which has to do with all of us." Many critics saw fit to trumpet the talent of the young film crew. In the Berliner Zeitung, for instance, Kurt Mühsam observed, "Robert Siodmak and Edgar Ulmer wield the authority of a director with remarkable aplomb." In the afternoon edition of the same paper, another critic asserted: "Billie Wilder has written a simple, but outstandingly composed screenplay, Schüfftan has performed splendid work on the camera, and Robert Siodmak, together with Edgar Ulmer, has directed very competently."

Although the picture was made at an especially fragile moment in history, between the recent stock market collapse and the rise of National Socialism, it evokes a strange sense of calm, purity and innocence. "People on Sunday can be understood," observes Lutz Koepnick, "as having allowed audiences to take a final breath before being caught in the vortex of violence and mass mobilization." The key concerns of the film, and of the film's characters—fighting over matinee idols, burning one's tongue on a hot dog, having one's portrait taken by a beach photographer, scrounging together enough money to spring for a boat ride—are indeed rather trivial when compared to the grand historical events unfolding off screen. This does not, however, make it in any way detached from its times. Its sustained focus on such comparatively banal matters is entirely in keeping with the Weimar preoccupation with leisure and the still rather new notion of "Weekend." Taken in this vein, People on Sunday stands as a commentary on such hit songs as "Wochenende und Sonnenschein" (Weekend and Sunshine)—Otto Stenzeel's original score was replete with pop standards of the day—and on the vivid photo portraiture of August Sander. It is also very much an exploration, in line with Siegfried Kracauer's 1929 study of Weimar Germany's white-collar workers, Die Angestellten (The Salaried Masses), of the new cultural habits of the petite bourgeoisie.

Despite the seemingly apolitical, even escapist nature of the film, there are overt strains of political satire. For example, relatively late in the story, after a quick cut to the Siegessäule (Victory Column), the central monument devoted to the glorious Prussian battles of the 1860s and 70s, we observe an elderly fellow walking along the Tiergarten's monumental promenade with hat and cane. Perhaps a veteran of the Great War, or merely someone who outlived Imperial Germany, he represents an era that was brought to a halt with the advent of Weimar, as he stands in front of the monuments, watching a procession of soldiers march by and then taking in the statues of the Prussian heroes. As Schüfftan's camera assumes the point of view of the old man, we zoom in on the imposing figures, thus gaining a privileged view. The elderly fellow finally sits down in front of former Duke of Prussia Georg Wilhelm (1595-1640), and removes his hat, as if to show respect and to offer a salute to the Prussian past. Many members of the Weimar-era audience would no doubt recognize these towering historical figures and might even recognize in the old fellow a playful allusion to Paul von Hindenburg, the former military strategist then serving as Reichspräsident and a notorious monarchist who embodied a brand of Weimar nostalgia for a lost epoch. As one critic put it, referring to the famed Weimar political satirist Kurt Tucholsky, the film has "a bit of Tucholsky-Germany."

Even if the film's meandering plot, almost more like an episode from a late twentieth-century American television sitcom like Seinfeld than from a Weimar feature film, eschews a more sophisticated, politically minded critique, People on Sunday certainly tested the limits of filmmaking at the time. It broke new ground in the final phase of silent film production, introducing a fresh model of independent cinema—well before the term, as we understand it today, even existed—and a bare-bones realism that had a deep impact both contemporaneously and for many years after. In the Berliner Tageblatt, the critic Eugen Szatmari took special delight in noting the ways in which the film undid studio production: "Young people got together and with laughably little means—without sets or ballrooms or opera galas, without stars, with a few human beings that they drew from their professions—they shot a film and achieved a total success for which one has to congratulate them and which hopefully will finally open up the eyes of the film industry."

Although this group of twentysomething cineastes would not effect the change hoped for by Szatmari, either in Weimar Germany or the Hollywood they fled to, the model they established with People on Sunday is one that has continued to be emulated internationally, from the French New Wave and New German Cinema up to the more systematic efforts in the name of Dogme 95. "It was Nouvelle Vague, even though it was only 1928 [sic]," Wilder told Tom Wood in an interview from the late 1960s. "We were dilettantes then." Along similar lines, filmmaker and critic Luc Moullet tells a story of how when he and Betrand Tavernier interviewed Ulmer in 1961, he suggested they all make a film together. "He wanted to remake Menschen am Sonntag with young [non-professional] French actors," he remarks. "He wanted me and Bertrand and a few others to write some scenes for that film." It ultimately got tucked away in an expansive file of unrealized projects.