Note: For an optimal reading experience, please ensure your browser is rendering the page at 100% zoom ("Cmd/Ctrl +/-").

Ossi against God and Goethe: Ernst Lubitsch's Mephistophela Project from 1920 and the Joys of Counterfactual Feminist Cinema

MAGGIE HENNEFELD

There's a scene early in Ernst Lubitsch's Die Austernprinzessin (The Oyster Princess, 1919) when Ossi (Oswalda) is enthusiastically demolishing a room. She decapitates a statue and shatters the base against the floor. Her father, Herr Quaker (a.k.a. "The Oyster King") storms in just in time for her to heave a stack of newspapers at his head. "Why exactly are you throwing all these newspapers at my head?", he protests. "Well, the vases have already all been broken!", Ossi responds logically. Devastated that her rival (daughter of the "Shoe Polish King") has wedded a count, Ossi unleashes her fury in a whirlwind of escalating destruction. That her father promises to "buy [her] a prince" only emboldens her demonic energy: "I'm so happy I could smash the whole house to pieces!" Toward that end, she crashes an antique chair against a desk littered with disheveled papers and books, smiling rapturously at the camera.

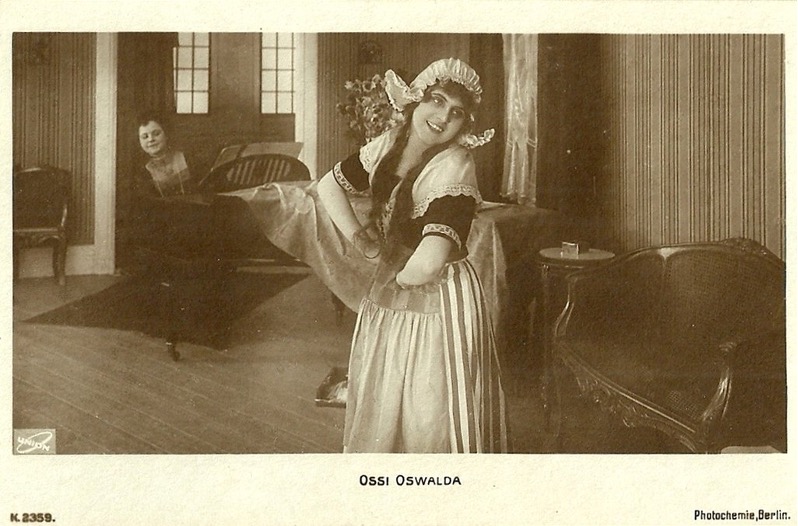

Like the fragile objects in the Oyster King's mansion, relatively few films by Ossi Oswalda (1898-1947) have survived intact and can still be seen today. According to the crucial filmography compiled by Molly Harrabin and Mary Hennessy for the Women Film Pioneers Project, only 23 of the 54 films in which Oswalda appeared between 1916 and 1933 still exist.1 Two are fragments, four feature brief cameos, and all but the Lubitsch titles remain difficult to access. When the Nazis came to power, Oswalda fled to Czechoslovakia. This marked the end of her acting career. She did write a screenplay for the Czech detective comedy Čtrnáctý u stolu (The Fourteenth at the Table, 1943), about a man named Čtrnáctý ("Fourteenth") who happens to be the fourteenth guest at a gathering of people who suffer from triskaidekaphobia, i.e., a fear of the number 13. If I could choose one more film in addition to those that have survived the ravages of Oswalda's filmography, my emphatic selection would be Mephistophela (1920).

A feminist Faust parody

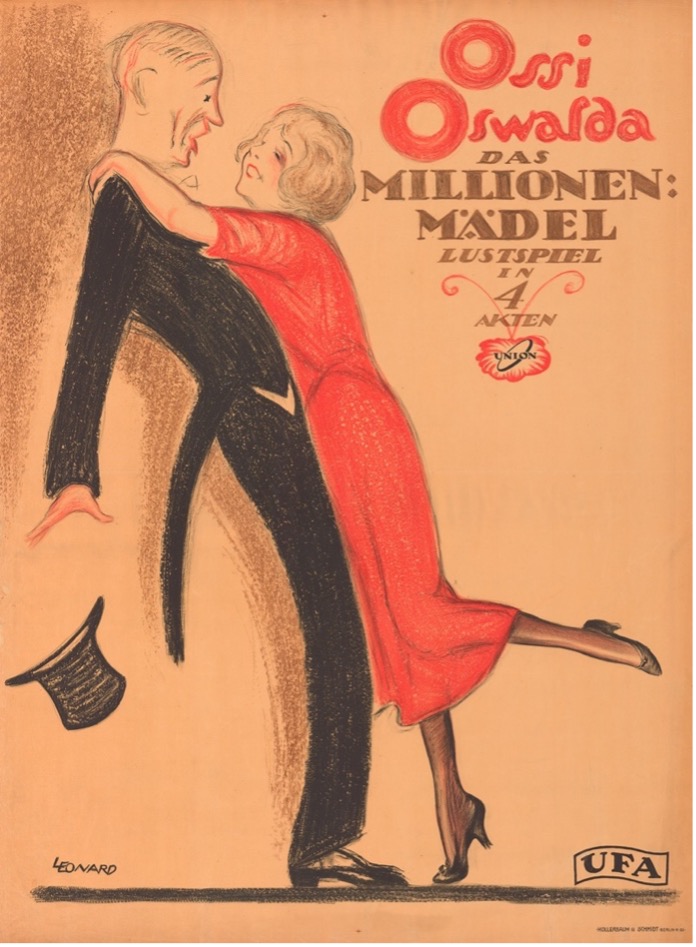

What happened to Mephistophela? In June 1920, almost exactly one year after the Berlin premiere of The Oyster Princess, the trade journal Der Kinematograph reported: "Hanns Kräly and Ernst Lubitsch are working on a grand fantasy comedy, Mephistophela, which humorously spins out the old Faust legend. The authors based the main character on Mephistophela from Heinrich Heine's ballet Doktor Faust. Ossi Oswalda plays the title role, Ernst Lubitsch directs."2

In Heine's "dance poem" from 1846, Faust conjures up the devil – and a female Mephisto named Mephistophela appears before him. Faust lets her teach him to dance, falls in love with her, elopes with her, and goes on wild adventures, only to be strangled by Mephistophela in the end and disappear into hell. This film, unfortunately, was never made.3

Whether or not Lubitsch had abandoned the Mephistophela project by the time he traveled to the US in 1922, his previous films with Oswalda suggest how the movie might have played out. In Lubitsch's brilliant historical comedies such as Die Austernprinzessin and Die Puppe (The Doll, 1919), Ossi Oswalda excels as a gleefully destructive force who challenges patriarchal authority. In the character of Ossi, one can easily envision a feminist Mephistophela "strangling" Faust by seducing him into feminist revolution. Many of Lubitsch's early comedies showcase the chaos that his liberated heroines unleash in stuffy male environments. Even in the (relatively) more subdued Ich möchte kein Mann sein (I Don't Want to Be a Man, 1918), Oswalda's character cross-dresses as a man and hilariously demolishes masculine conventions. If Mephistophela had followed through on the gender swapping of Heine's source, one can imagine Oswalda seducing Faust into "falling" upward into enlightenment rather than hellward into damnation. Oswalda's signature comedic style was highly physical and anarchic. Lubitsch biographer, Scott Eyman, credits her with pioneering the kind of "slapstick" that people today associate with male comics.4 Regarding the unrealized potential for a slapstick Mephistophela, one might echo Murnau's Dr. Frankenstein when his creation stirs to life: "Oh, what monstrous beauty! Watch them: they are truly ridiculous!5

This essay is about a film that was never made – and how we might think about unmade films as a particular kind of feminist film history. What would it mean to write about films that don't exist? To spend time with the "could have beens" and "what ifs" of women's film history? To follow Gaylyn Studlar's famous questions about child stars – "Could there have been other Shirleys?" – but redirected toward women filmmakers and comedians across the spectrum: "Could there have been other Ossis?" Studlar ponders the untold "countless number of girls" who "might have been" child stars, "but whom we will never know precisely because they weren't selected for stardom."6 In a similar spirit, I wonder about all the feminist film comedies that "might have been," but which got lost, destroyed, or were never realized due to political circumstances like fascism and the violent upheavals of the twentieth century. As feminist film scholar, Allyson Nadia Field, points out: speculative film histories require "a more generous disposition toward evidence, a willingness to construct knowledge from fragments and ephemera, and to write histories closely tethered to surviving evidence."7

The kinds of "evidence" and "ephemera" that survive from unmade films like Mephistophela include trade journal announcements, script fragments, costume tests, and promotional materials. Such materials invite the feminist film historian to practice what Saidiya Hartman calls "critical fabulation.": the scholarly method of "playing with and rearranging the basic elements of the story" in order to jeopardize "the status of the event, to displace the received or authorized account, and to imagine what might have happened."8 Film history tends to privilege the "important" and the "enduring," which has meant privileging male filmmakers over female ones, dramas over comedies, "high" art over "low" entertainment. Serious consideration of unmade films offers one method for undoing some of these hierarchies.9

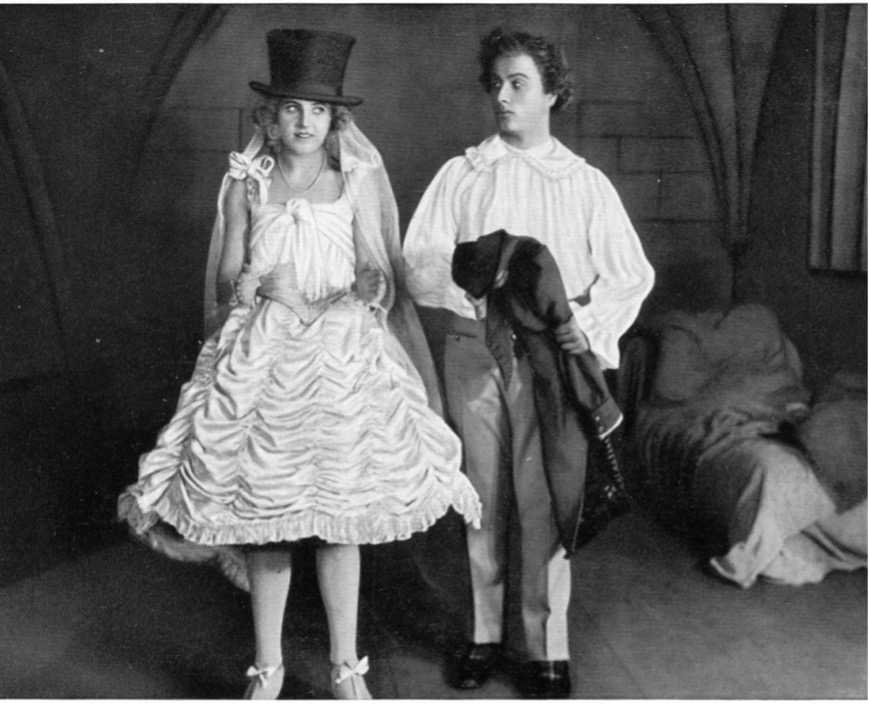

What might we learn if we treated Lubitsch's unmade Mephistophela (1920) as seriously as his completed films? How might an analysis of the film that never was shed new light on the ones that did get made? This essay argues that Mephistophela would have been Lubitsch's most explosive gender-bending comedy, and that thinking about this unrealized project offers important context for understanding Oswalda's roles in Die Puppe and other Lubitsch comedies. Whereas Die Puppe is a whimsical fantasy with comedic horror elements, Mephistophela would have been a horror fantasy with comedic elements – supernatural physical comedy, one might say, instead of psychological horror.10

Oswalda's modernist cinema

Another way to approach Mephistophela is to consider how the film might have contributed to the development of modernist cinema more broadly. Oswalda's comedic style was notably experimental and avant-garde, often incorporating elements that wouldn't become common in mainstream cinema until much later. Her performances frequently broke the fourth wall, included moments of surreal physical comedy, and experimented with non-linear narrative structures.

For example, in Die Puppe, there are several sequences where Oswalda's character seems to be aware that she's in a film – she looks directly at the camera, responds to off-screen cues, and generally behaves in ways that call attention to the constructed nature of cinema. This kind of meta-theatrical self-awareness was quite radical for 1919 and anticipates developments in avant-garde cinema that wouldn't emerge until the 1960s and 1970s.

Similarly, Oswalda's physical comedy often incorporated elements of dance and performance art that were ahead of their time. Her movements were highly stylized and choreographed, but in ways that seemed spontaneous and improvisational. This combination of precision and apparent spontaneity would later become a hallmark of modernist performance, but Oswalda was experimenting with these techniques in the context of popular commercial cinema.

If Mephistophela had been completed, it's likely that it would have pushed these experimental elements even further. The supernatural premise would have provided opportunities for even more surreal and avant-garde sequences, potentially including early experiments with special effects, non-realistic set design, and expressionistic lighting. The film might have served as a bridge between the experimental theatrical traditions of early 20th-century German culture and the emerging possibilities of cinema as an art form.

This is another reason why unmade films like Mephistophela deserve serious scholarly attention. They represent not just lost entertainment, but lost opportunities for artistic innovation and experimentation. By reconstructing what these films might have looked like, we can begin to imagine alternative histories of cinema that might have been more experimental, more diverse, and more politically progressive than the actual history that unfolded.

Contemporary resonances: One of the most striking things about researching Mephistophela in 2024 is how contemporary its themes feel. The film's planned focus on a powerful female figure who uses supernatural abilities to challenge patriarchal authority resonates strongly with current interests in feminist horror, women's anger, and female rage as a source of creative and destructive power.

Moreover, the film's apparent interest in gender fluidity and supernatural transformation speaks to contemporary discussions about gender identity and the possibilities for transcending binary gender categories. While we can't know exactly how Lubitsch and Oswalda would have handled these themes, the basic premise of the film – a female devil figure who seduces and transforms male characters – suggests a radical questioning of traditional gender roles that feels remarkably prescient.

The story of Ernst Lubitsch's unmade Mephistophela ultimately reminds us that film history is not just about what was, but about what might have been – and what still might be. By taking seriously the creative possibilities that were never fully realized, we can develop a richer and more inclusive understanding of cinema's past, and perhaps also a more expansive vision of its future.

In the end, perhaps that's the most valuable lesson that unmade films like Mephistophela can teach us: that possibility itself is a form of cultural inheritance, and that by attending to the unrealized potentials of the past, we can expand our sense of what might be possible in the future. The feminist devil that Ossi Oswalda never got to play continues to haunt the margins of film history, waiting for new generations of filmmakers to discover her and bring her to life in new forms.

Footnotes

1 I am grateful to Molly Harrabin and Mary Hennessy for sharing their research and expertise with me. Their article on Oswalda's career for the Women Film Pioneers Project website will be published shortly. For feminist perspectives on Oswalda's comedies, see, among others, Heide Schlüpmann: ""Ich möchte kein Mann sein" (I don't want to be a man). Ernst Lubitsch, Sigmund Freud, and early German comedy." In: Frank Kessler, Sabine Lenk, Martin Loiperdinger (eds.): Früher Film in Deutschland (Early Film in Germany). Basel 1993 (KINtop. Yearbook for Research into Early Film 1), pp. 75–92; Janet McCabe: "Regulating Hidden Pleasures and "Modern" Identities. Imagined Female Spectators, Early German Popular Cinema, and The Oyster Princess (1919)." In: Randall Halle, Margaret McCarthy (eds.): Light Motives. German Popular Cinema in Perspective. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2003, pp. 24-40; Claudia Preschl: Lachende Körper. Komikerinnen im Kino der 1910er Jahre. Vienna 2008, esp. pp. 151-156.

2 Announcement by the Union projection company in Der Kinematograph, no. 701/702, June 27, 1920.

3 See the note on this and other unrealized Lubitsch projects in Wolfgang Jacobsen: "Filmografie." In: Hans Helmut Prinzler, Enno Patalas (eds.): Lubitsch. Munich, Lucerne 1984, pp. 200–223, there pp. 222f. and Scott Eyman: Ernst Lubitsch. Laughter in Paradise. Baltimore: Wayne State University Press, 2000, p. 381. The film title can also be found in the Filmportal, but without any indication that it was never made.

4 Joseph McBride: How Did Lubitsch Do It? New York: Columbia University Press, 2018, p. 138. Many thanks to Molly Harrabin for pointing this out. See also Eyman: Ernst Lubitsch, pp. 87-89.

5 See the 12-minute "Screen Tests for Marguerite and Faust" (1923), shown in 2023 in the series "Cento anni fa" (100 Years Ago), curated by Stefan Drößler and Oliver Hanley.

6 Gaylin Studlar: "Oh, "Doll Divine": Mary Pickford, Masquerade, and the Pedophilic Gaze." In: Camera Obscura, Vol. 16, No. 3, 2001, pp. 196-227.

7 Allyson Nadia Field: "Editor's Introduction: Sites of Speculative Encounter." In: Feminist Media Histories, Issue 8, No. 2, 2022, p. 3.

8 Saidiya Hartman: "Venus in Two Acts." In: Small Axe, No. 26, June 2008, pp. 1-14; Samantha N. Sheppard: "Changing the Subject: Lynne Nottage's By the Way, Meet Vera Stark and the Making of Black Women's Film History." In: Feminist Media Histories, No. 2, 2022, p. 14–42; Alix Beeston and Stefan Solomon (eds.): Incomplete. The Feminist Possibilities of the Unfinished Film. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2023.

9 The need to write about German films that are no longer visible applies particularly to comedies by and starring women, which were once hugely popular. These comedies are now almost entirely absent from an otherwise male-dominated canon with its preference for "important," serious topics.

10 Devan Scott aptly describes Die Puppe as "Expressionist birthday cake" in his excellent podcast, How Would Lubitsch Do It?, which chronologically covers Lubitsch's entire filmography, including lost (but not unmade) films.